Anatomy of a disaster

Two decades later, Iraqis are still paying the price for Bush's ill-judged war

Twenty years ago, on March 19, 2003, a US-led coalition invaded Iraq. Two claims were put forward by the Americans and their British allies to justify the unprecedented overthrow by force of the leadership of a sovereign state: that President Saddam Hussein possessed and was preparing to use weapons of mass destruction, and that his regime had been complicit in the Sept. 11 attacks on America by Al-Qaeda in 2001.

Both claims proved to be false.

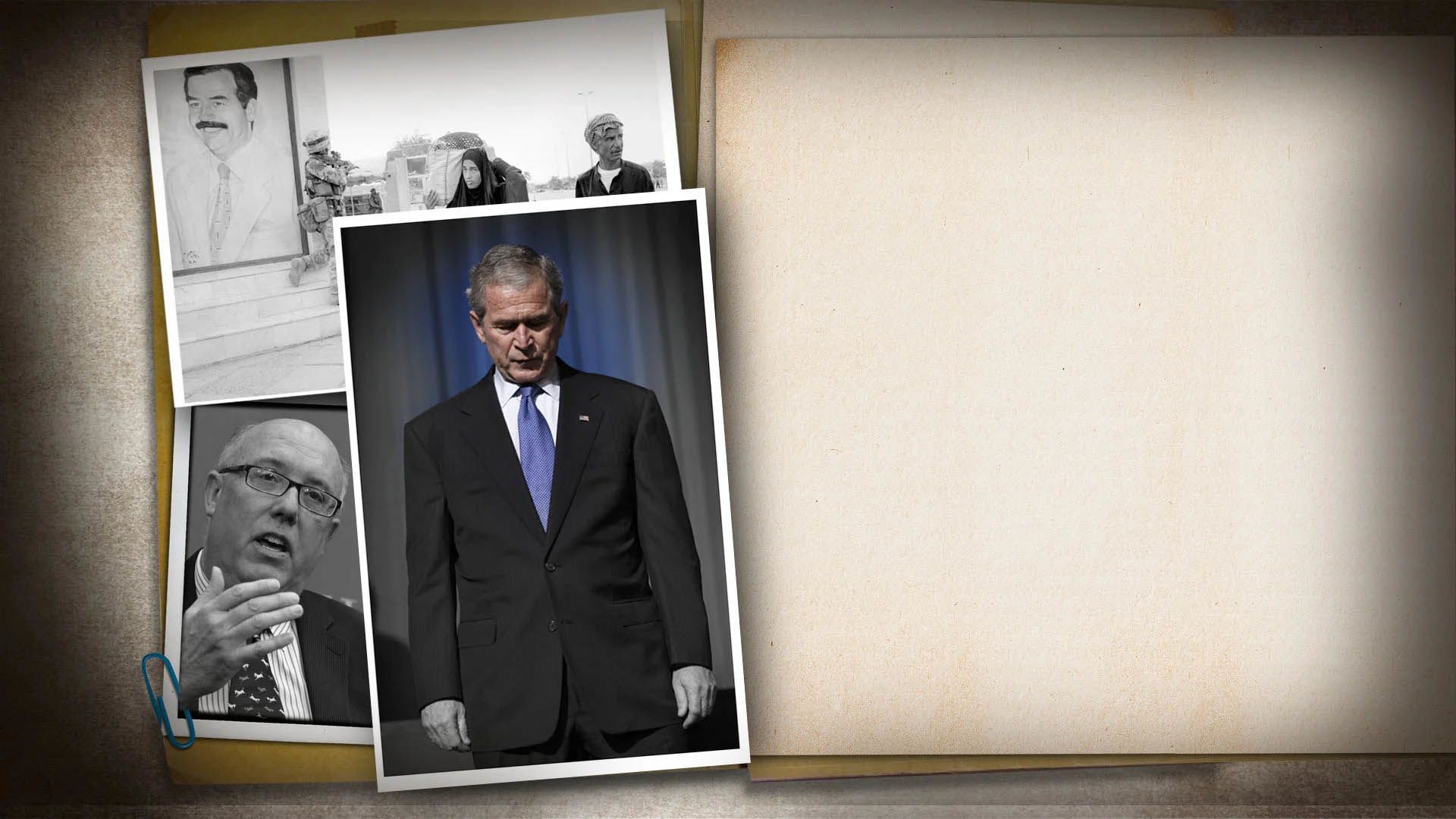

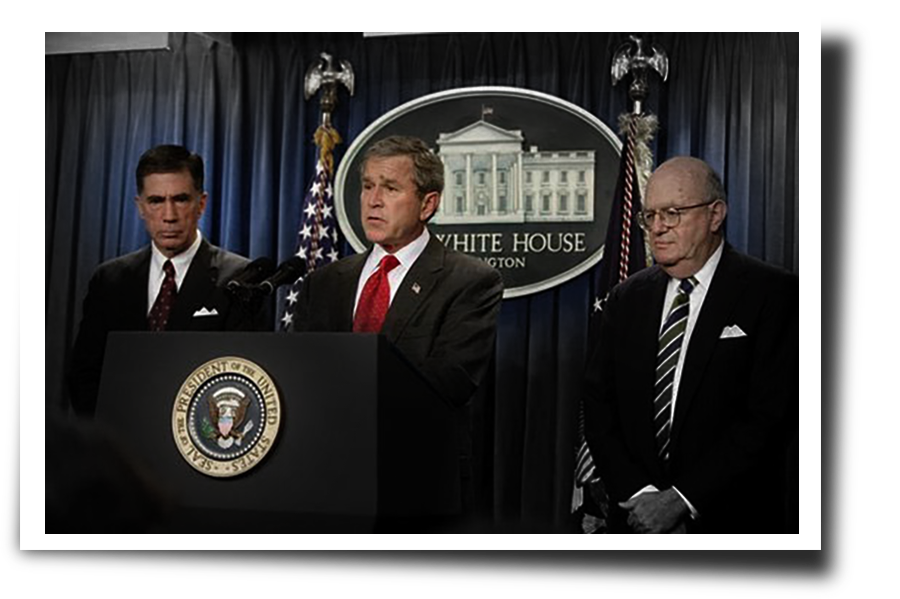

On Sept. 18, 2001, one week after the 9/11 attacks, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the Saudi ambassador to Washington, visited US President George W. Bush in the White House.

As Bruce Riedel, a member of Bush’s National Security Council, would later recall, when the president told the ambassador that he thought Iraq was behind the attacks, “Bandar was visibly perplexed.”

The prince, Riedel said, “told Bush that the Saudis had no evidence of any collaboration between (Al-Qaeda leader) Osama bin Laden and Iraq. Indeed, their history was of being antagonists.”

But Bush “was obsessed with the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and deliberately misled the American people about who was responsible for the 9/11 attack ... Consequently, the United States went to war in Iraq on a false pretense that it was somehow avenging those killed by Al-Qaeda.”

In an article published on the Lawfare blog on Sept. 11, 2021, Riedel wrote that after meeting Bush at the White House “Bandar told me privately that the Saudis were very worried about where Bush’s obsession with Iraq was going. The Saudis were alarmed that attacking Iraq would only benefit Iran and set in motion severe destabilizing repercussions across the region.”

It was a prediction that would come to pass, with horrifying consequences that echo down to this day.

This is the story of how the US and its allies falsified or deliberately misrepresented intelligence to justify an invasion that, in hindsight, proved unjustifiable.

It is also the story of the human cost of that invasion, for which the people of Iraq are continuing to pay a heavy price.

As a study of the war published in 2019 by the US Army would conclude, only one winner emerged from the years of civil war and insurgency that followed the US invasion and occupation: Iran.

Twenty years ago, on March 19, 2003, a US-led coalition invaded Iraq. Two claims were put forward by the Americans and their British allies to justify the unprecedented overthrow by force of the leadership of a sovereign state: that President Saddam Hussein possessed and was preparing to use weapons of mass destruction, and that his regime had been complicit in the Sept. 11 attacks on America by Al-Qaeda in 2001.

Both claims proved to be false.

On Sept. 18, 2001, one week after the 9/11 attacks, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the Saudi ambassador to Washington, visited US President George W. Bush in the White House.

As Bruce Riedel, a member of Bush’s National Security Council, would later recall, when the president told the ambassador that he thought Iraq was behind the attacks, “Bandar was visibly perplexed.”

The prince, Riedel said, “told Bush that the Saudis had no evidence of any collaboration between (Al-Qaeda leader) Osama bin Laden and Iraq. Indeed, their history was of being antagonists.”

But Bush “was obsessed with the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and deliberately misled the American people about who was responsible for the 9/11 attack ... Consequently, the United States went to war in Iraq on a false pretense that it was somehow avenging those killed by Al-Qaeda.”

In an article published on the Lawfare blog on Sept. 11, 2021, Riedel wrote that after meeting Bush at the White House “Bandar told me privately that the Saudis were very worried about where Bush’s obsession with Iraq was going. The Saudis were alarmed that attacking Iraq would only benefit Iran and set in motion severe destabilizing repercussions across the region.”

It was a prediction that would come to pass, with horrifying consequences that echo down to this day.

This is the story of how the US and its allies falsified or deliberately misrepresented intelligence to justify an invasion that, in hindsight, proved unjustifiable.

It is also the story of the human cost of that invasion, for which the people of Iraq are continuing to pay a heavy price.

As a study of the war published in 2019 by the US Army would conclude, only one winner emerged from the years of civil war and insurgency that followed the US invasion and occupation: Iran.

The crooked path to war

SEPT. 11, 2001

We’re going to go to a live picture from New York City, apparently a plane has crashed into the World Trade Center in New York ... with limited information at this point we don’t know about injuries, but obviously this has the potential for being a major disaster ...”

– Fox News at 8:52 a.m., with one of the first news reports of the 9/11 attacks.

SEPT. 11, 2001

Hit S. H. @same time; Not only UBL; near term target needs — go massive — sweep it all up — need to do so to hit anything useful.”

– Stephen Cambone, aide to US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, records Rumsfeld’s first thoughts after the Pentagon was hit: to attack Saddam Hussein as well as Osama bin Laden.

SEPT. 14, 2002

I was in the Oval Office with the president when he talked to Tony Blair. And in the middle of the conversation with Tony Blair about 9/11, George Bush says, ‘We’re going to attack Iraq too.’ The British prime minister was completely taken aback. Now, in time, of course, he would come around.”

– Speaking in 2021, Bruce Riedel, former CIA analyst and National Security Council adviser to the president in 2001, recalls a telephone conversation between George W. Bush and Tony Blair three days after the 9/11 attacks on America.

SEPT. 18, 2001

A week after 9/11, Saudi ambassador, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, came to the White House to see Bush. Vice President Richard Cheney and (former US National Security Adviser Condoleezza) Rice were there as well. My note says the president ‘clearly thinks Iraq must be behind this. His questions to Bandar show his bias.’ Bandar was visibly perplexed. He told Bush that the Saudis had no evidence of any collaboration between Osama bin Laden and Iraq. Indeed, their history was of being antagonists.”

– Bruce Riedel, former CIA analyst and National Security Council adviser to the president in 2001, writing in 2021 on the anniversary of 9/11, recalls Saudi consternation at the US suggestion of Iraqi complicity in the attacks.

NOV. 8, 2002

The Security Council ... recognizing the threat Iraq’s non-compliance with Council resolutions and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and long-range missiles poses to international peace and security ... decides to afford Iraq a final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations under relevant resolutions of the Council; and accordingly decides to set up an enhanced inspection regime with the aim of bringing to full and verified completion the disarmament process established by resolution 687 (1991) and subsequent resolutions of the Council.”

– UN Security Council Resolution 1441, drawn up by the UK and the US and adopted unanimously by the Council.

FEB. 3, 2003

We issued further intelligence over the weekend about the infrastructure of concealment (in Iraq). I hope that people have some sense of the integrity of our security services. They are not publishing this, or giving us this information, and making it up. It is the intelligence that they are receiving, and we are passing it on to people. In the dossier that we published last year, and again in the material that we put out over the weekend, it is very clear that a vast amount of concealment and deception is going on.”

– Tony Blair speaking in the House of Commons upon the publication of what became known as the "Dodgy dossier."

FEB. 5, 2003

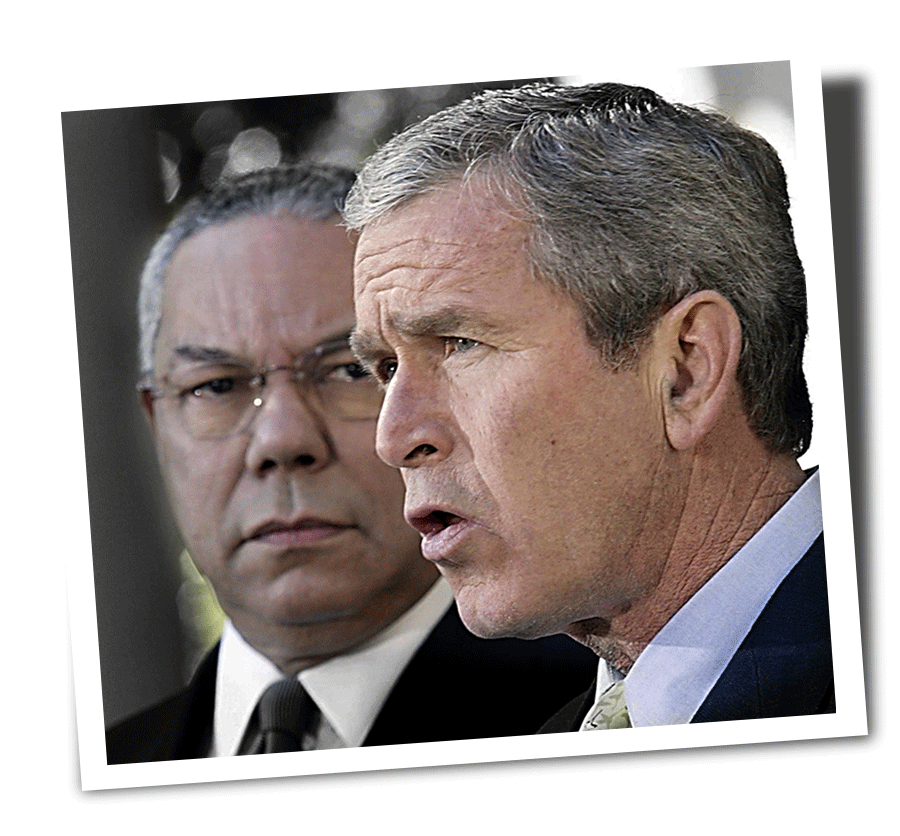

I would call my colleagues’ attention to the fine paper that the United Kingdom distributed yesterday, which describes in exquisite detail Iraqi deception activities ... There can be no doubt that Saddam Hussein has biological weapons and the capability to rapidly produce many more. And he has the ability to dispense these lethal poisons and diseases in ways that can cause massive death and destruction ... I (also) want to bring to your attention the sinister nexus between Iraq and the Al-Qaeda terrorist network ... Iraq today harbors a deadly terrorist network headed by Abu Musab Zarqawi.”

– US Secretary of State Colin Powell's presentation to UN Security Council, “Iraq: Failing to Disarm.”

FEB. 7, 2003

Downing Street was last night plunged into acute international embarrassment after it emerged that large parts of the British government’s latest dossier on Iraq – allegedly based on intelligence material – were taken from published academic articles, some of them several years old.”

– The Guardian, “UK war dossier a sham, say experts.”

FEB. 17, 2003

The fracturing of the Western alliance over Iraq and the huge antiwar demonstrations around the world this weekend are reminders that there may still be two superpowers on the planet: the United States and world public opinion. President Bush appears to be eyeball to eyeball with a tenacious new adversary: millions of people who flooded the streets of New York and dozens of other world cities to say they are against war based on the evidence at hand.”

– The New York Times, after more than 30 million people around the world marched on Feb. 15 to protest against the coming invasion of Iraq.

MARCH 7, 2003

After three months of intrusive inspections, we have to date found no evidence or plausible indication of the revival of a nuclear weapons program in Iraq.”

– Mohamed El-Baradei, head of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

MARCH 17, 2003

The United Nations Security Council has not lived up to its responsibilities, so we will rise to ours. In recent days, some governments in the Middle East have been doing their part. They have delivered public and private messages urging the dictator to leave Iraq, so that disarmament can proceed peacefully. He has thus far refused. All the decades of deceit and cruelty have now reached an end. Saddam Hussein and his sons must leave Iraq within 48 hours. Their refusal to do so will result in military conflict, commenced at a time of our choosing.”

– In a televised address, President George W. Bush delivers a final ultimatum to Saddam Hussein.

MARCH 19, 2003

My fellow citizens. At this hour American and coalition forces are in the early stages of military operations to disarm Iraq, to free its people and to defend the world from grave danger. On my orders, coalition forces have begun striking selected targets of military importance to undermine Saddam Hussein's ability to wage war. These are the opening stages of what will be a broad and concerted campaign.”

– In an address to the nation from the Oval Office of the White House, President Bush announces the start of "Operation Iraqi Freedom."

The lies exposed

MAY 29, 2003

On July 17, 2003, David Kelly, a biological warfare expert and UN weapons inspector who claimed the British government had "sexed up" its dossier on weapons of mass destruction, was found dead in a wood near his home in Oxfordshire. His death was ruled a suicide.

On July 17, 2003, David Kelly, a biological warfare expert and UN weapons inspector who claimed the British government had "sexed up" its dossier on weapons of mass destruction, was found dead in a wood near his home in Oxfordshire. His death was ruled a suicide.

We’ve been told by one of the senior officials in charge of drawing up that dossier that actually the government probably knew that that 45-minute figure was wrong, even before it decided to put it in. What this person says, is that a week before the publication date of the dossier, it was actually rather a bland production. It didn’t say very much more than was public knowledge already and Downing Street, our source says, ordered it to be sexed up, to be made more exciting and ordered more facts to be, er, discovered.”

– BBC reporter Andrew Gilligan on Radio 4 “Today” program.

JUNE 25, 2003

The story that I ‘sexed up’ the dossier is untrue. The story that I ‘put pressure on the intelligence agencies’ is untrue. The story that we somehow made more of the 45-minute command and control point than the intelligence agencies thought was suitable, is untrue.”

– Alastair Campbell, Blair’s former press secretary, giving evidence to the UK Foreign Affairs Committee.

JULY 7, 2003

Artwork imagining Tony Blair taking a selfie in front of blazing Iraqi oilfields featured in "People Power: Fighting for Peace," an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum, London, in March 2017, exploring anti-war protests.

Artwork imagining Tony Blair taking a selfie in front of blazing Iraqi oilfields featured in "People Power: Fighting for Peace," an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum, London, in March 2017, exploring anti-war protests.

We conclude that the 45 minutes claim did not warrant the prominence given to it in the dossier, because it was based on intelligence from a single, uncorroborated source. We recommend that the Government explain why the claim was given such prominence ... We conclude that continuing disquiet and unease about the claims made in the September dossier are unlikely to be dispelled unless more evidence of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction programmes comes to light.”

– British House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee report, “The Decision to go to War in Iraq.”

JAN. 28, 2004

It turns out we were all wrong, and that is most disturbing.”

– Testimony to the US Senate Armed Services Committee of David Kay, appointed by the CIA to lead the 1,400-strong Iraq Survey Group, which after the invasion failed to find evidence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Kay resigned on Jan. 23, 2004.

JAN. 29, 2004

Condoleezza Rice, promoted in January 2005 to the role of US Secretary of State, poses with Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani and US soldiers during a visit to Arbil in May 2005. (AFP)

Condoleezza Rice, promoted in January 2005 to the role of US Secretary of State, poses with Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani and US soldiers during a visit to Arbil in May 2005. (AFP)

I think that what we have is evidence that there are differences between what we knew going in and what we found on the ground.”

– US national security adviser Condoleezza Rice, who advocated for the invasion of Iraq.

MARCH 3, 2004

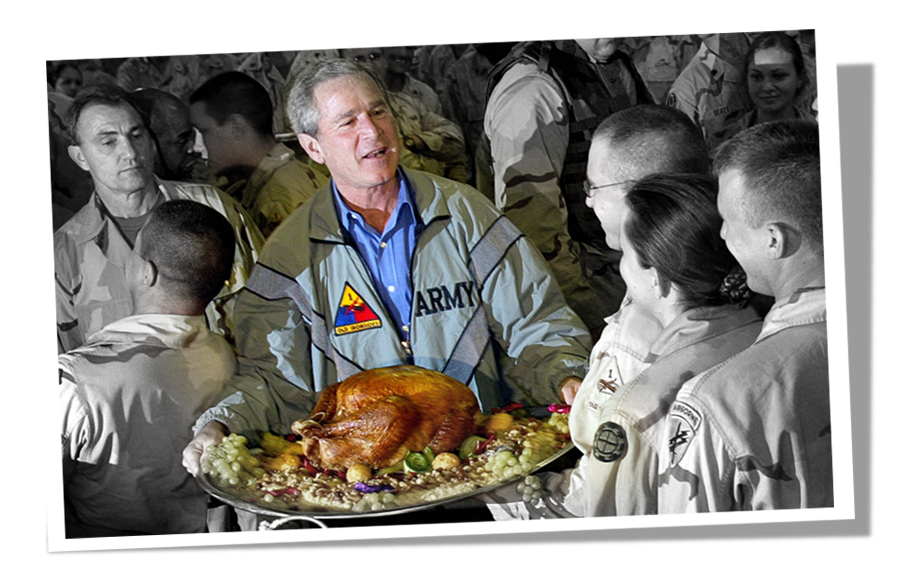

In a surprise visit to Iraq on Nov. 27, 2003, President George W. Bush serves Thanksgiving turkey to US troops stationed at Baghdad airport. (AFP)

In a surprise visit to Iraq on Nov. 27, 2003, President George W. Bush serves Thanksgiving turkey to US troops stationed at Baghdad airport. (AFP)

It’s about coming clean with the American people. (President Bush) should say, ‘we were mistaken, and I am determined to find out why.”

– David Kay, after resigning as leader of America's Iraq Survey Group.

MARCH 17, 2004

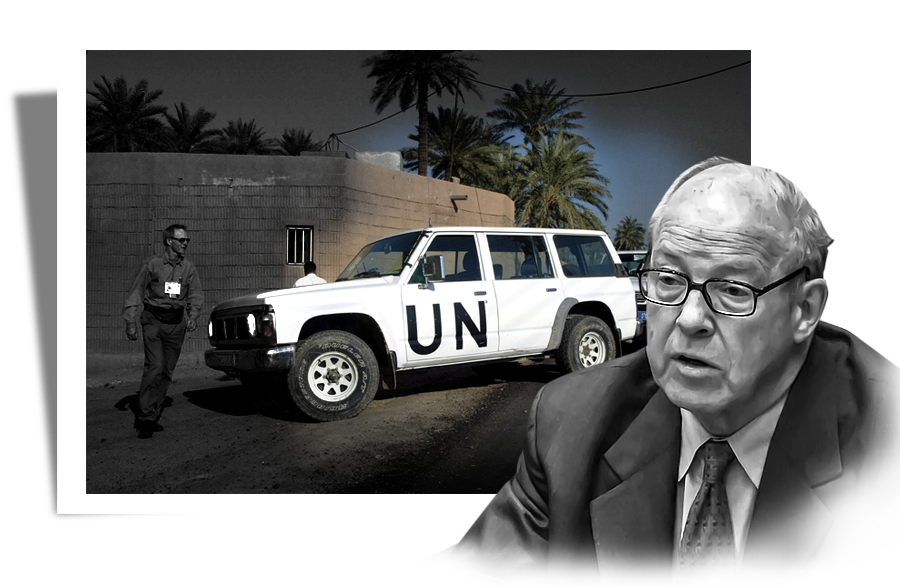

In the build-up to the war, Saddam Hussein and the Iraqis were cooperating with UN inspections ... There were about 700 inspections, and in no case did we find weapons of mass destruction.”

– Hans Blix, leader of the UN Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission.

JULY 7, 2004

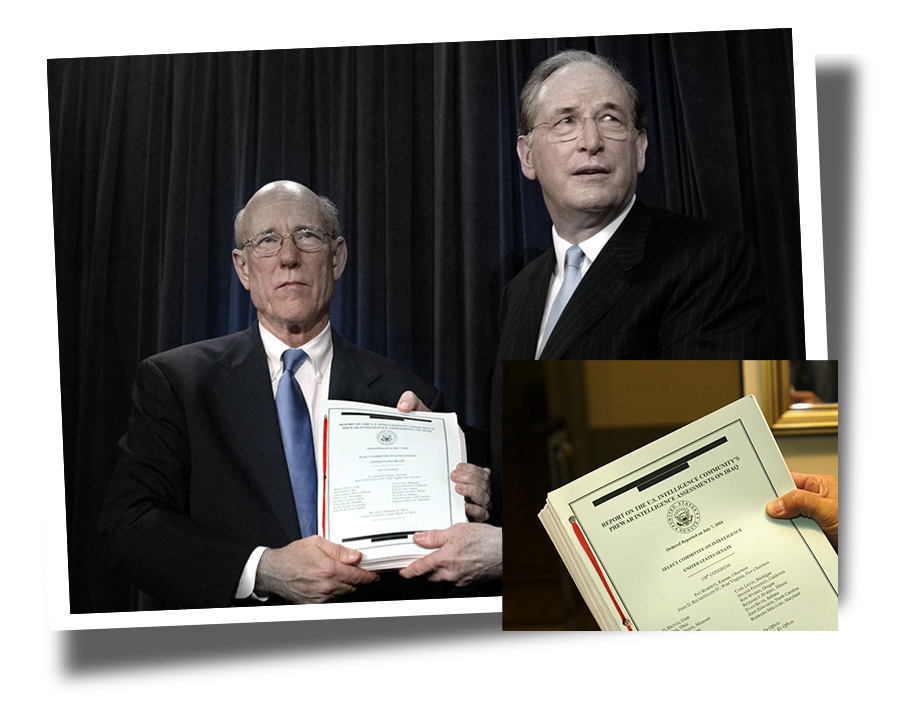

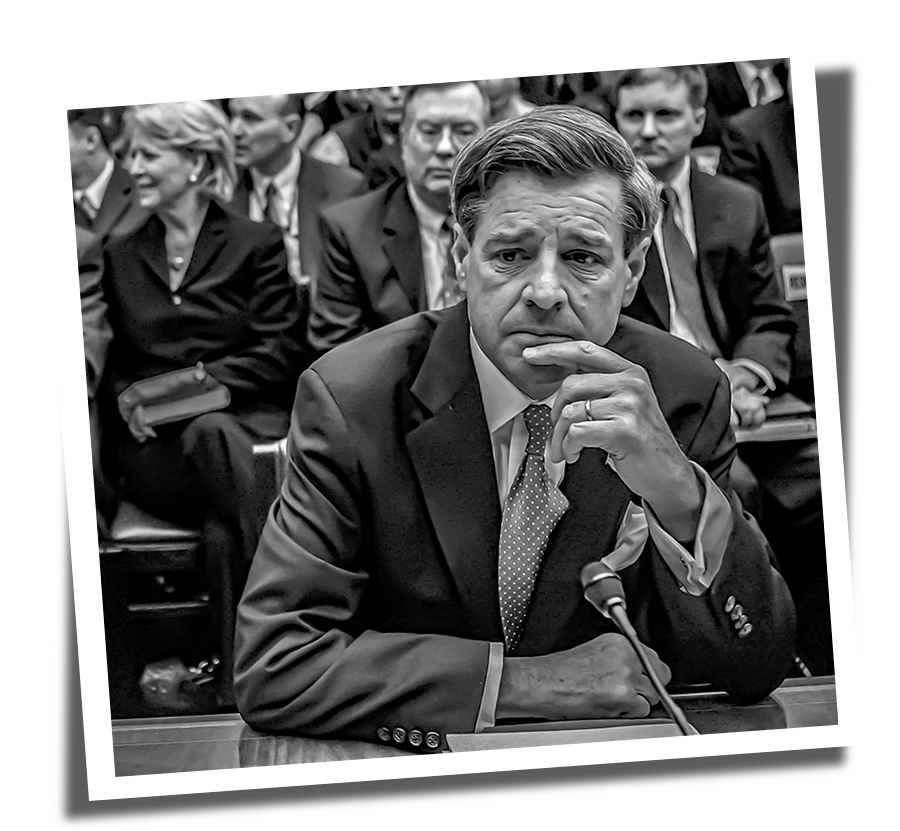

Senators Pat Roberts, left, and John D. Rockefeller IV present the Senate Select Committee's damning report on the failures of US intelligence in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq.

Senators Pat Roberts, left, and John D. Rockefeller IV present the Senate Select Committee's damning report on the failures of US intelligence in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq.

Most of the major key judgments in the intelligence community’s October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate, ‘Iraq’s continuing programs for weapons of mass destruction,’ either overstated, or were not supported by, the underlying intelligence reporting.”

– US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, “Report on the US intelligence community’s pre-war intelligence assessments on Iraq.”

JULY 22, 2004

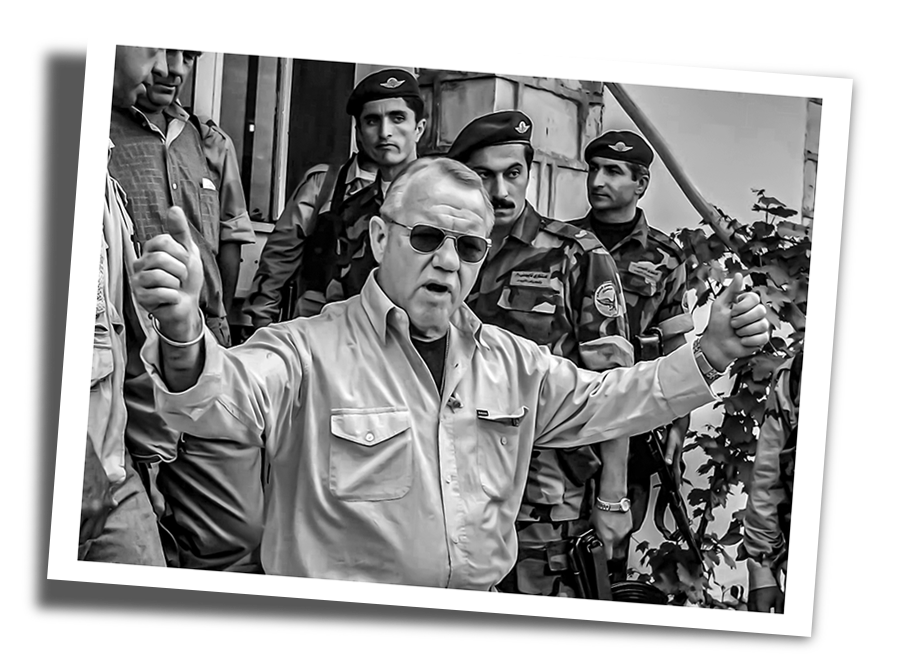

Paul Wolfowitz, US deputy secretary of defense, visits Mosul on July 21, 2003. He was one of the first members of the Bush administration to advocate for an invasion of Iraq.

Paul Wolfowitz, US deputy secretary of defense, visits Mosul on July 21, 2003. He was one of the first members of the Bush administration to advocate for an invasion of Iraq.

Paul (Wolfowitz, US deputy secretary of defense), was always of the view that Iraq was a problem that had to be dealt with, and he saw this as one way of using this event as a way to deal with the Iraq problem.”

– Statement by US Secretary of State Colin Powell, in report published by the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States.

OCT. 6, 2004

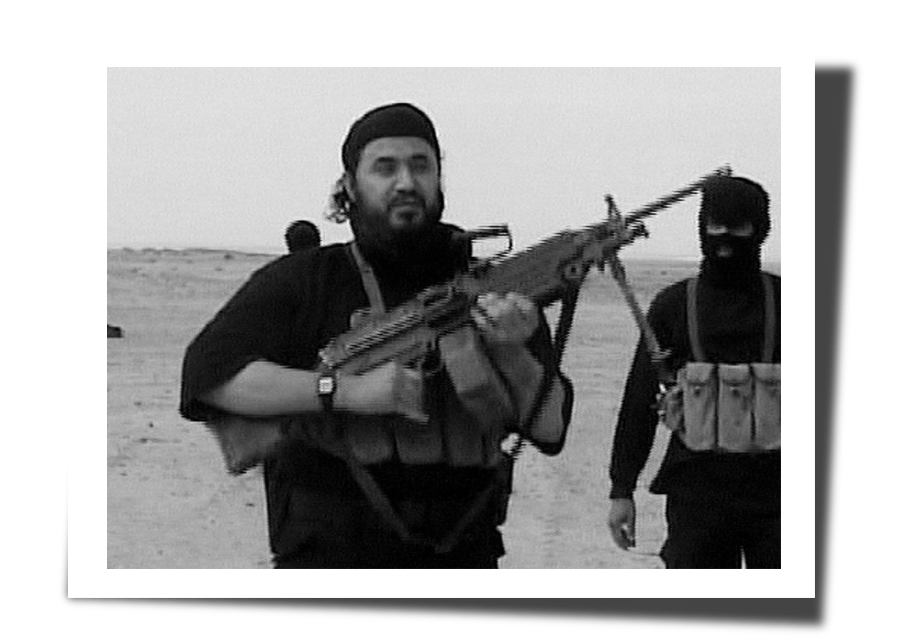

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq, who came to the country only after the invasion and embarked on a campaign of terror against Shiites. He was killed in a targeted US bombing on June 7, 2006 (AFP)

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq, who came to the country only after the invasion and embarked on a campaign of terror against Shiites. He was killed in a targeted US bombing on June 7, 2006 (AFP)

A CIA report has found no conclusive evidence that former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein harbored Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, which the Bush administration asserted before the invasion of Iraq.”

– Reuters report.

MARCH 31, 2005

President Bush names former Democratic senator Chuck Robb, left, and former judge Laurence Silberman as co-chairs of an independent commission to examine pre-war intelligence on Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. (AFP)

President Bush names former Democratic senator Chuck Robb, left, and former judge Laurence Silberman as co-chairs of an independent commission to examine pre-war intelligence on Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. (AFP)

The Intelligence Community was dead wrong in almost all of its pre-war judgments about Iraq's weapons of mass destruction. This was a major intelligence failure. Its principal causes were the Intelligence Community's inability to collect good information about Iraq's WMD programs, serious errors in analyzing what information it could gather, and a failure to make clear just how much of its analysis was based on assumptions, rather than good evidence."

– Conclusion of the Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction, established by presidential order on February 6, 2004.

SEPT. 8, 2005

I’m the one who presented it on behalf of the United States to the world, and (it) will always be a part of my record. It was painful. It’s painful now ... There were some people in the intelligence community who knew at the time that some of those sources were not good, and shouldn’t be relied upon, and they didn’t speak up. That devastated me.”

– After resigning as US Secretary of State, Colin Powell told Barbara Walters on ABC News that he regretted the speech he made to the UN Security Council in February 2003, in which he made the case for invading Iraq.

NOV. 6, 2007

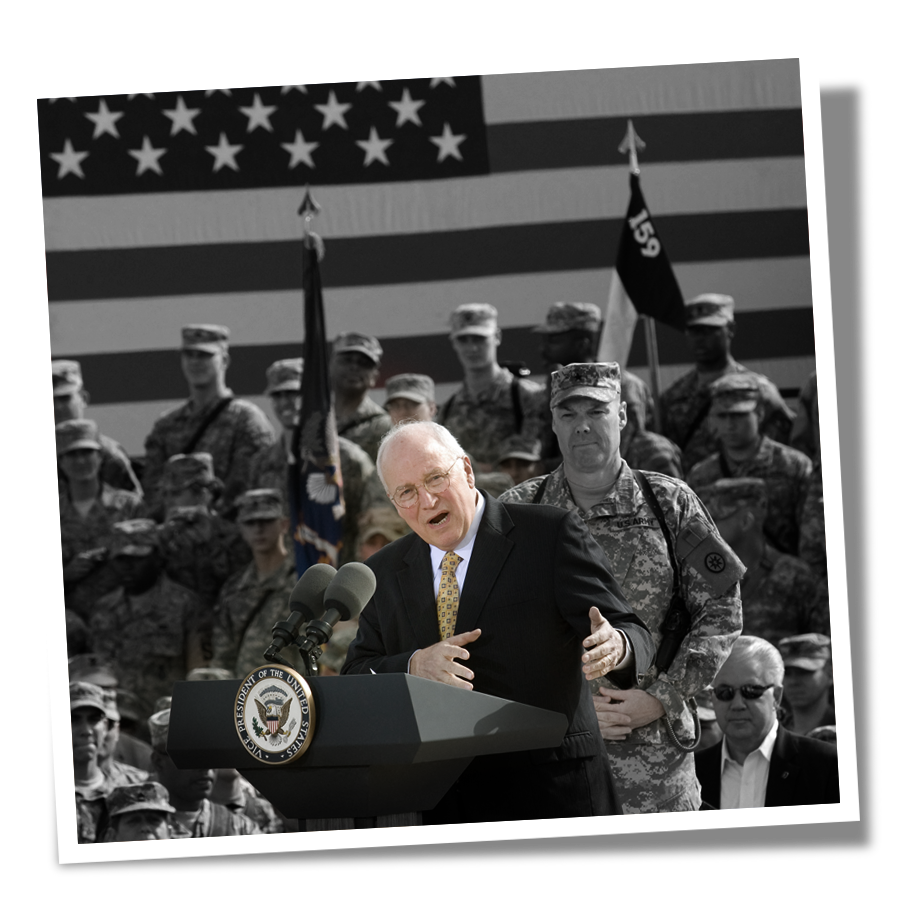

US Vice President Dick Cheney addresses American troops at Balad Air Base, Iraq, on March 18, 2008. (AFP)

US Vice President Dick Cheney addresses American troops at Balad Air Base, Iraq, on March 18, 2008. (AFP)

Richard B. Cheney, in violation of his constitutional oath to faithfully execute the office of vice president of the United States ... has purposely manipulated the intelligence process to deceive the citizens and Congress of the United States by fabricating a threat of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction to justify the use of the United States Armed Forces against the nation of Iraq in a manner damaging to our national security interests.”

– Text of impeachment resolution filed by US Representative Dennis Kucinich against still-serving Vice President Richard Cheney, co-sponsored by 25 fellow Democrats and one independent Representative. The resolution, which was not considered by the Judiciary Committee, expired in 2009.

JULY 6, 2016

Over 10,000 anti-war protestors gather outside London's High court on Aug. 19, 2003, as the Hutton inquiry investigates the suicide of weapons expert David Kelly, found dead after revealing that claims about Iraqi WMDs were exaggerated by Tony Blair’s government. (Getty)

Over 10,000 anti-war protestors gather outside London's High court on Aug. 19, 2003, as the Hutton inquiry investigates the suicide of weapons expert David Kelly, found dead after revealing that claims about Iraqi WMDs were exaggerated by Tony Blair’s government. (Getty)

We have concluded that the UK chose to join the invasion of Iraq before the peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted. Military action at that time was not a last resort ... The judgments about Iraq’s capabilities ... were presented with a certainty that was not justified.”

– Report of the Iraq Inquiry, commissioned by Gordon Brown, Blair’s successor as British prime minister, and chaired by Sir John Chilcot.

Ibrahim Al-Marashi

Aftermath

APRIL 2, 2003:

“Okay, Bubba, we’re here. Now what?”

– Lt. Gen. William Wallace calls Coalition Forces Land Component Command for instructions after the US 3rd Infantry Division seizes downtown Baghdad.

US military planners had estimated it would take between 70 and 120 days to overthrow Saddam Hussein, who had ruled Iraq for the best part of three decades. In fact, his army was routed, and Saddam driven into hiding, in just 21 days.

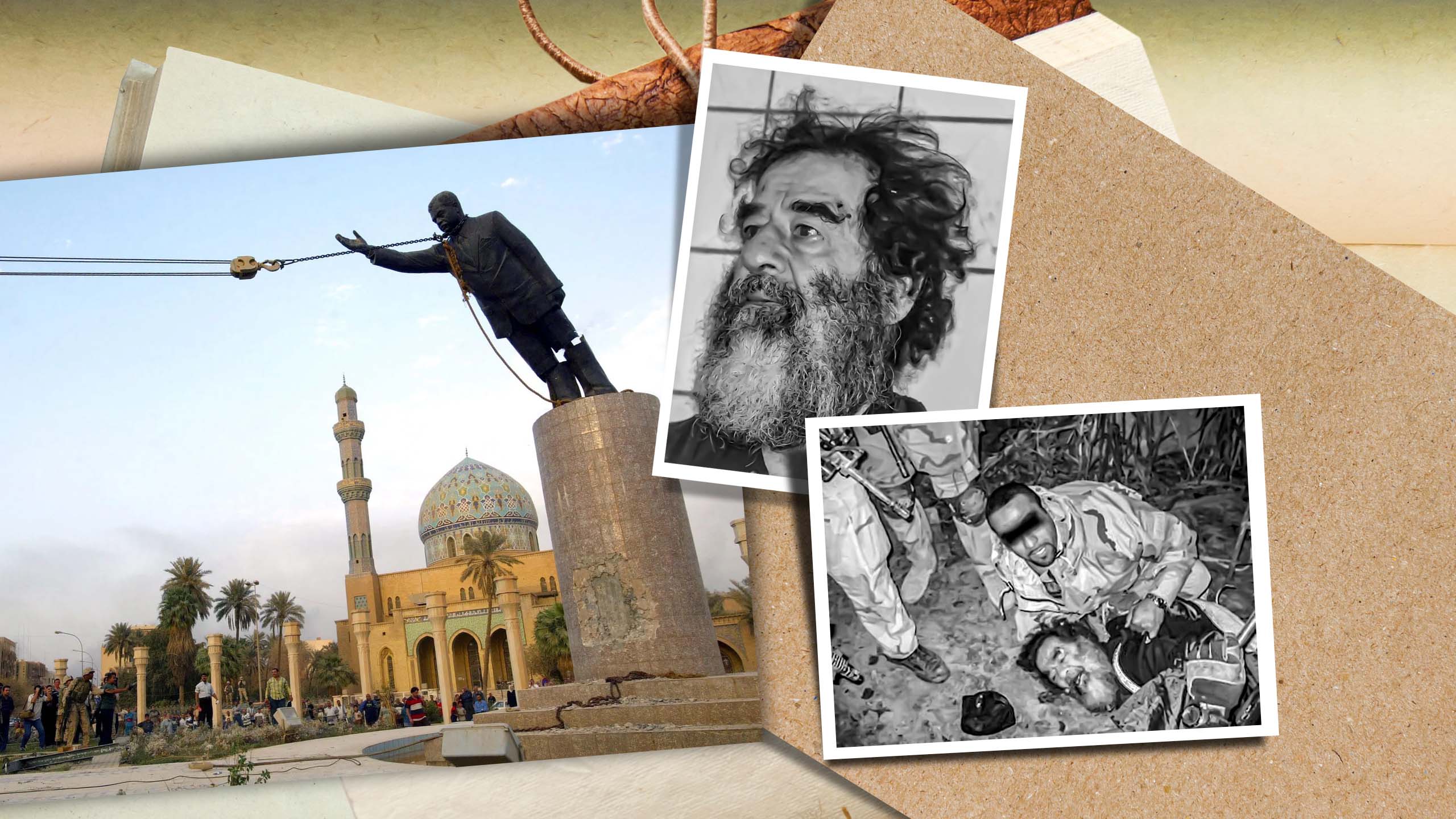

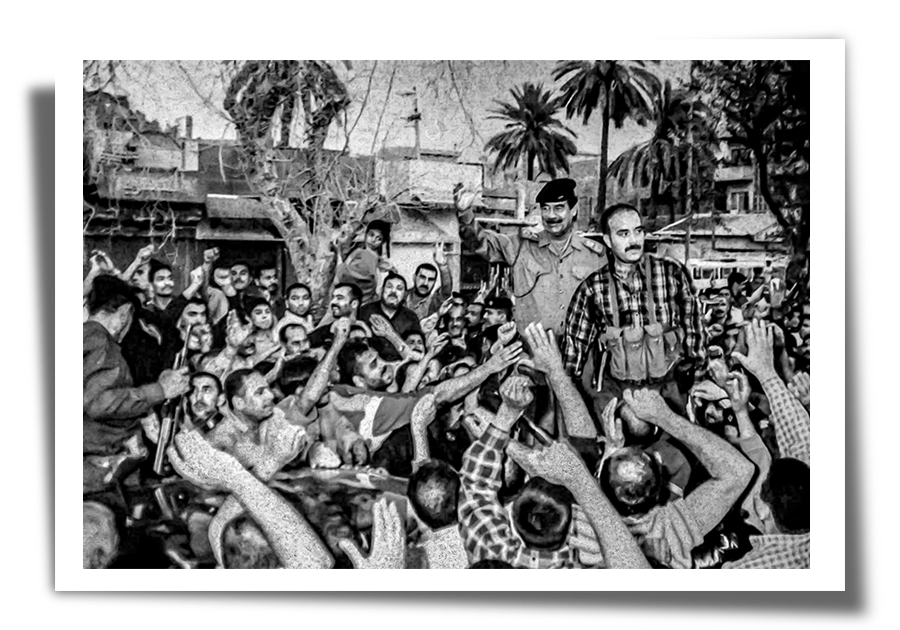

On April 9, exactly three weeks after the opening shots had been fired in Operation Iraqi Freedom, the dictator made one final public appearance, greeting supporters in front of television cameras in the Baghdad neighborhood of Adhamiya.

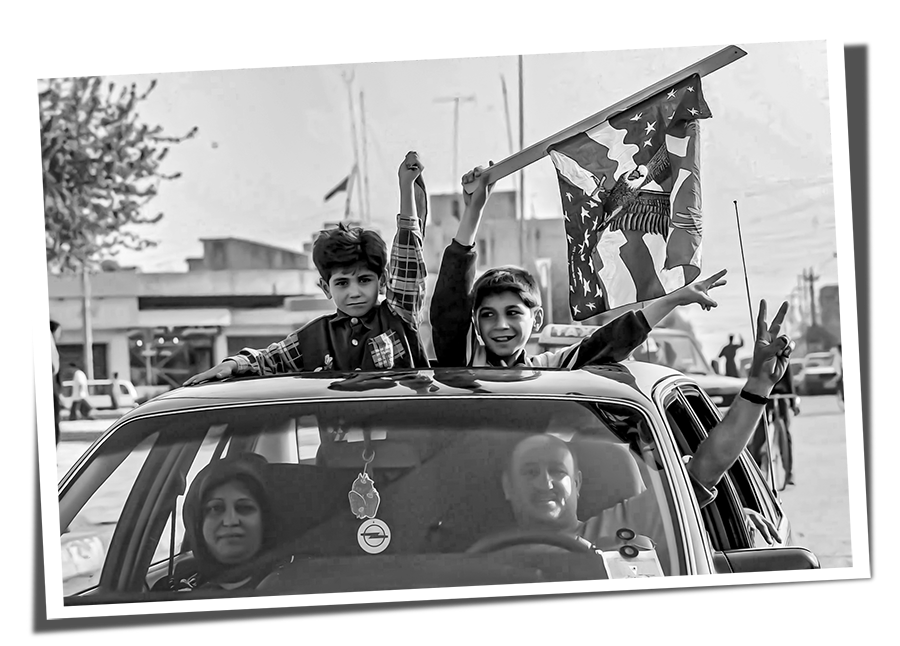

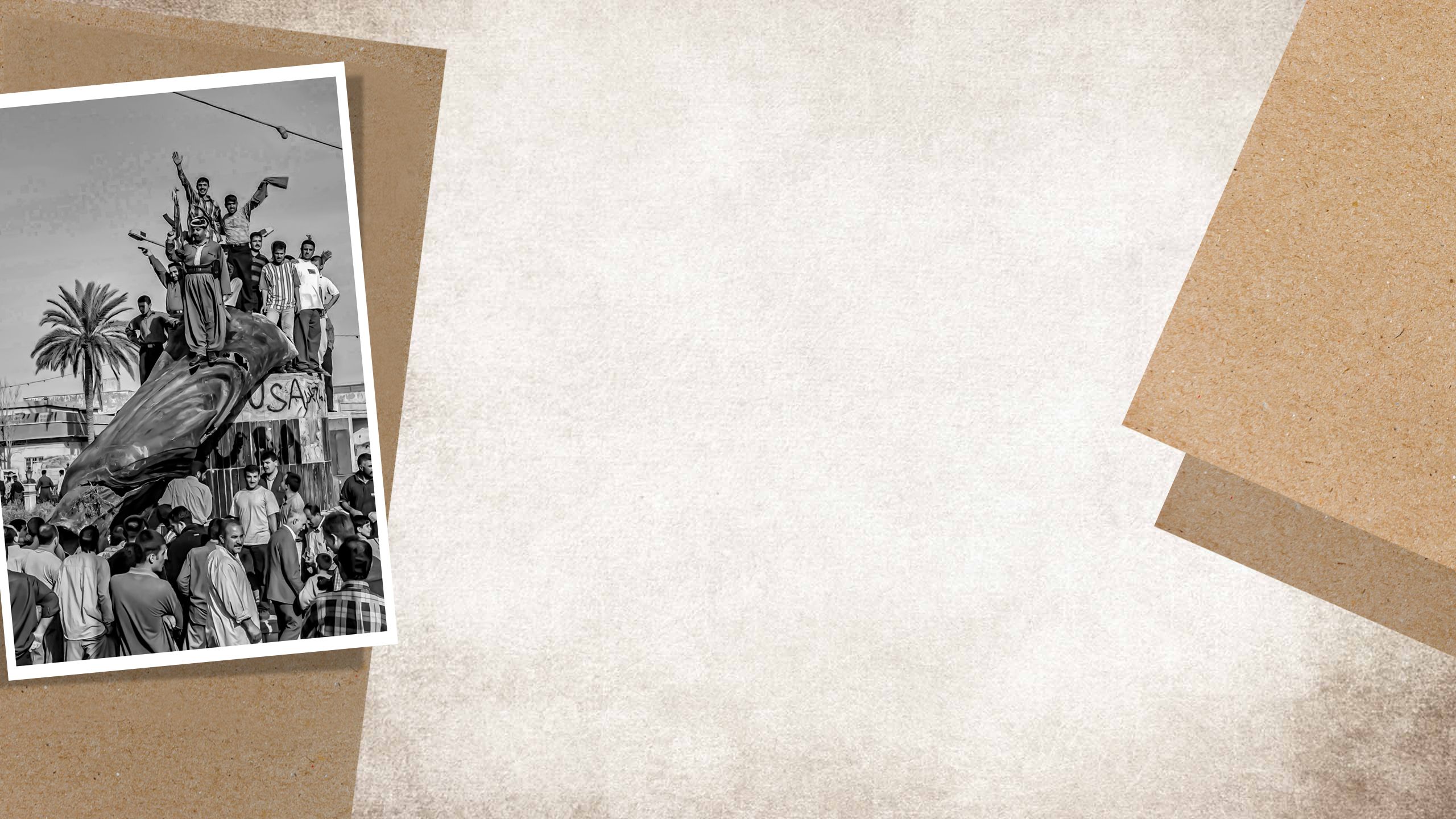

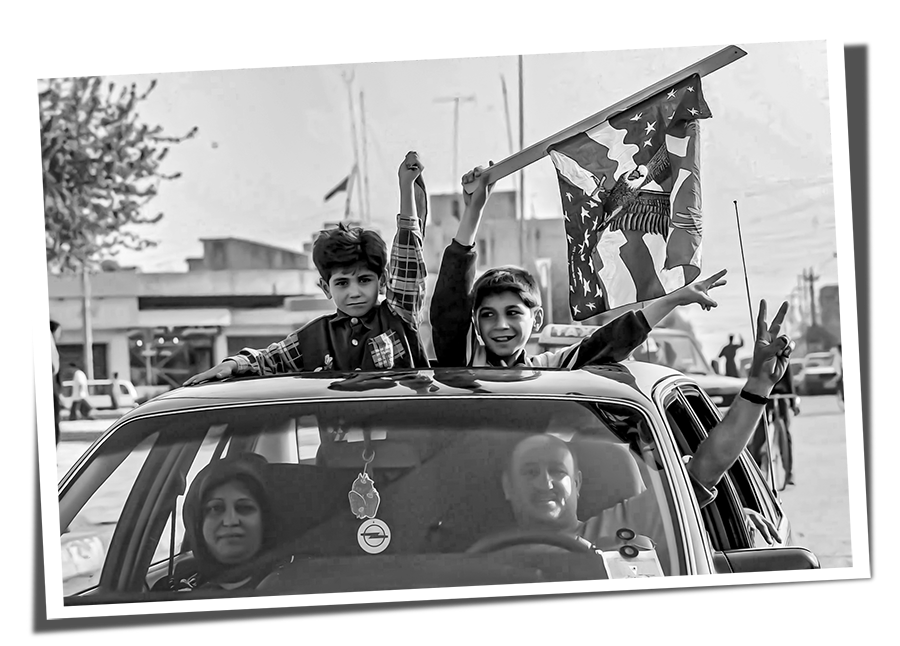

That same day, resistance in Baghdad collapsed, the capital fell to the Americans and, here and there, Iraqis began celebrating in the streets.

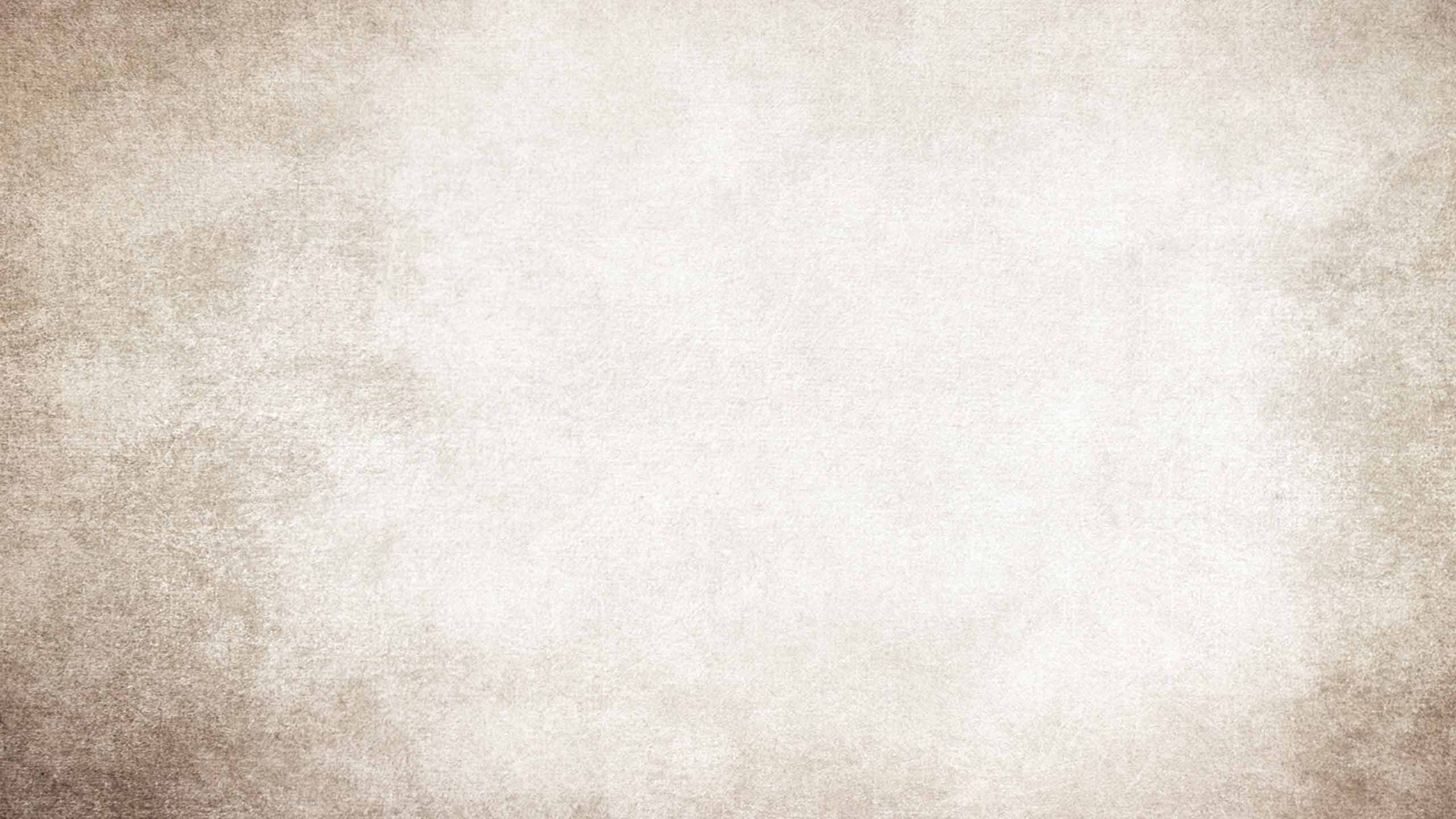

In one iconic incident on April 9, crowds attacked a 12-meter-tall statue of the deposed dictator in the city’s Firdos Square, which was finally pulled down with the help of a passing unit of US Marines, equipped with an M88 armored recovery vehicle.

Saddam would not be seen again until Dec. 13, when, after seven months on the run, US special forces found him, disheveled, heavily bearded, and confused, hiding in a hole in the ground in a farm compound near his hometown of Tikrit, 150 kilometers northwest of Baghdad.

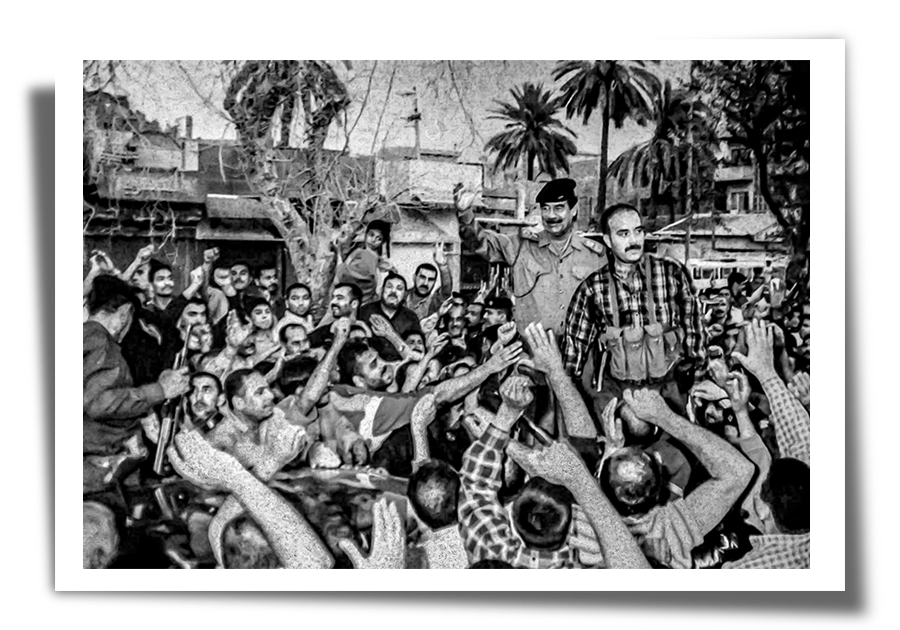

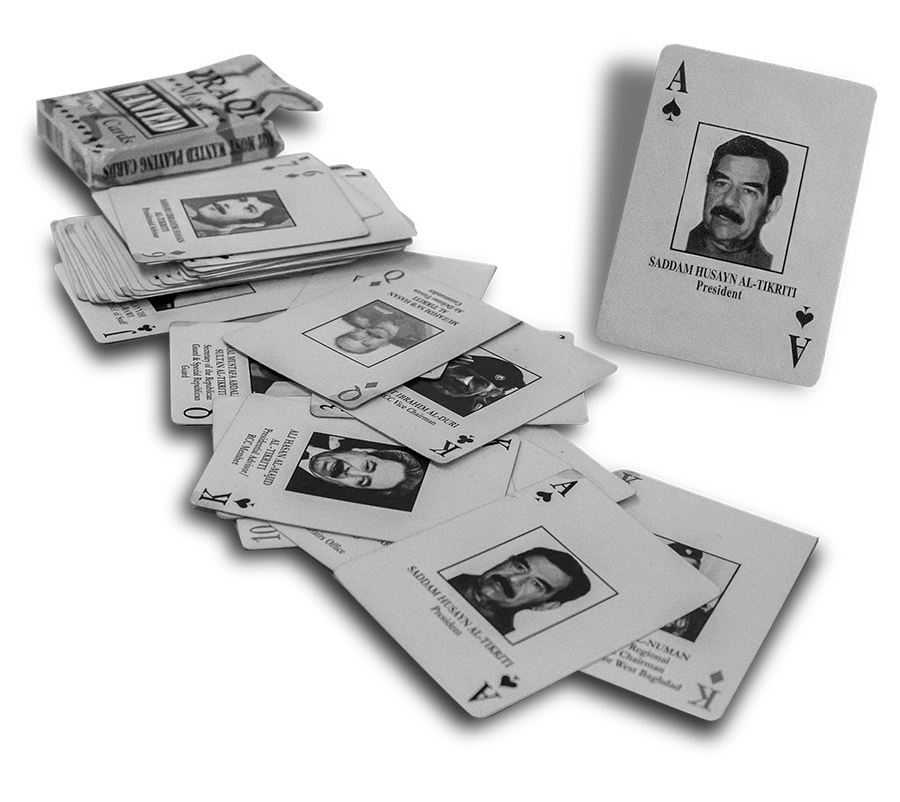

The Americans had issued a set of 55 playing cards, each bearing the face of a wanted member of the regime and advertising the bounty on offer for turning them in. Saddam, the ace of spades in the pack, was worth $25 million.

But the man who told the Americans where he was hiding, who was Saddam’s bodyguard and a relative, reportedly got nothing, because he revealed his location only after being arrested and interrogated.

The reward offered for Saddam’s sons, Qusay and Uday, the ace of hearts and the ace of clubs in the pack, was $15 million each. They had been killed on July 22 by US soldiers who stormed the house in Mosul in which they were hiding after they refused to surrender. Qusay’s 14-year-old son Mustafa died with them.

The owner of the house, a former regime loyalist who had taken them in, was reported to have been paid in full for betraying them.

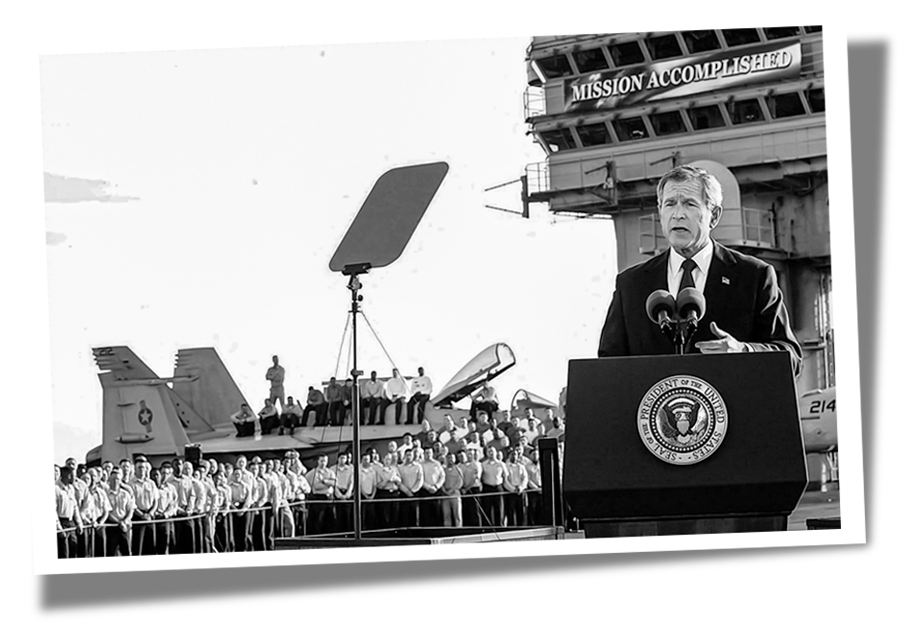

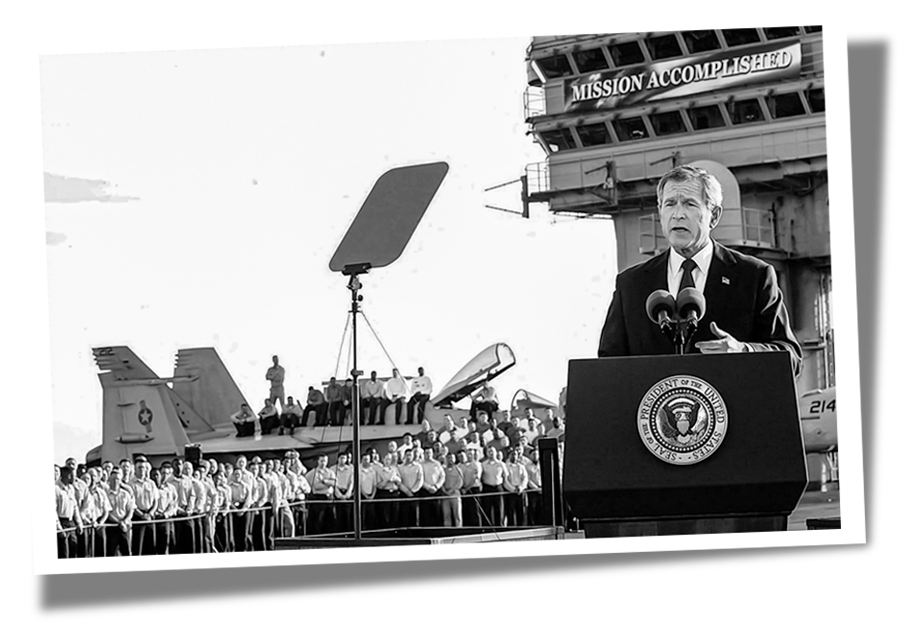

On May 1, Bush was back on television once again, broadcasting from the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, which had just returned from the Gulf.

Standing in front of a large banner emblazoned with the stars and stripes and bearing the words “Mission accomplished,” he announced that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended.”

To the whoops and cheers of the crew, he added: “In the battle of Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed.”

It would prove to be a hubristic claim that would come back to haunt the president, and thousands of American and Iraqi families.

The apparent victory had come at a light cost for the coalition. By May 1, just 172 Americans had been killed, along with 33 British troops, and about 24 Kurdish Peshmerga fighters.

Speaking from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, President Bush declares victory in Iraq. (AFP)

Speaking from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, President Bush declares victory in Iraq. (AFP)

It was a different story for the Iraqis, of course, both those in and out of uniform. As many as 45,000 combatants had been killed, along with an estimated 7,200 civilians.

But the war was far from over and, thanks to a tragedy of errors, the body count was set to rise.

It soon became painfully clear to the Americans that overthrowing Saddam had been the easy part.

Few in the region and beyond mourned the passing of the era of Saddam, who had ruled Iraq with a rod of iron and for years had relentlessly persecuted the Kurds in the north of the country.

His invasion of Iran in 1980 had led to a bloody war that had cost the lives of at least half a million Iraqis and as many or more Iranians before it ended in stalemate eight years later, and in 1990 he had brought the entire region to the threshold of catastrophe when he invaded Kuwait in a bid to seize its oil fields.

But in the vacuum left behind in 2003 by the neutering of the ousted dictator’s ruling Baath party, the dismissal of the entire Iraqi army and the lack of serious US planning for a post-war Iraq, the country swiftly descended into years of insurgency, sectarian violence, and civil war, creating the perfect conditions for the emergence of Daesh and the insidious rise of Iranian influence in Iraq’s politics.

It was left to a surprisingly frank two-volume study of the conduct of the war, commissioned by the US Army’s senior leadership in 2013 and finally published in 2018, to admit what the politicians who had started the conflict could never bring themselves to concede.

The human and material cost of the conflict had been “staggering.” But, they added, it was in terms of “geostrategic consequences” that the war had generated its most “profound consequences. With Iraq no longer a threat, Iran’s destabilizing influence has quickly spread.”

In fact, they concluded, “an emboldened and expansionist Iran appears to be the only victor. Iraq, the traditional regional counterbalance for Iran, is at best emasculated, and at worst has key elements of its government acting as proxies for Iranian interests.”

The story of the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq is the story of a catalogue of blunders and missteps by a US administration that assumed Iraqis would welcome democracy with open arms, but reckoned without the agendas of the multiple factions in the country which, freed from the ruthless chains that had bound them together, now sought power and payback for the decades of repression they had endured.

With hindsight, the four-phase plan for the invasion of Iraq that was presented to President Bush and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld by CENTCOM commander Gen. Tommy Franks at Camp David on Dec. 28. 2001 was dangerously naive.

Phases one to three were not the problem: build a coalition of willing partners and supporters, embark on “psychological and military deception operations designed to encourage segments of Iraqi society and its armed forces not to resist”, and, finally, invade Iraq, destroy any forces that had not melted away and “decapitate the Iraqi regime.”

But phase four, so-called post-combat “stability operations,” including the transition of power to a new Iraqi government, was a different matter.

As the clear-eyed US Army analysis of the war noted, too little thought was given to this crucial phase, while such thought that had been given was fatally undermined by a series of flawed assumptions.

Key among these was that “US forces would be welcomed as liberators, and that the Iraqi army would help provide security under a new, more enlightened Iraqi government.”

As a result, the US forces that had focused “on their immediate objectives of destroying the Iraqi military and forcing regime change, were not prepared for the complicated phase four they were about to face.”

Wrong-footed by “overly optimistic strategic assessments that the Iraqi population would welcome the coalition and resume normal activities quickly,” coalition commanders were surprised to find themselves faced with “widespread public disorder and looting,” even as they continued to battle remaining pockets of resistance in Baghdad and Anbar, and much of the north of the country had yet to be secured.

At first, the predictions of a warm welcome appeared valid.

“Once it became clear that Saddam was no longer in power, Iraqi citizens began wild celebrations in the streets of Baghdad and other liberated areas,” read the official US Army analysis of the campaign.

But celebration quickly morphed into something else. Coalition troops “were unprepared for the utter dissolution of public order that followed,” and within days of the collapse of the regime, “Baghdad and other areas of Iraq descended into chaos.”

Baath Party and Iraqi government offices and public facilities, including police stations and hospitals, were attacked, looted and, in some cases, set on fire. Looters descended on the National Museum of Baghdad, and hundreds of priceless artifacts were stolen, many of which would turn up later on international markets.

Here and there, riots began to flare, which in many cases appeared to the military to be orchestrated attempts to provoke a violent response from coalition troops.

Within 10 days of Baghdad’s fall on April 9, religious leaders from various sects had begun jockeying for positions of power in cities throughout the country.

The confusion in post-invasion occupied Iraq was typified by the hurried creation of the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, set up at short notice by the US Department of Defense to support the transition from military to civilian control.

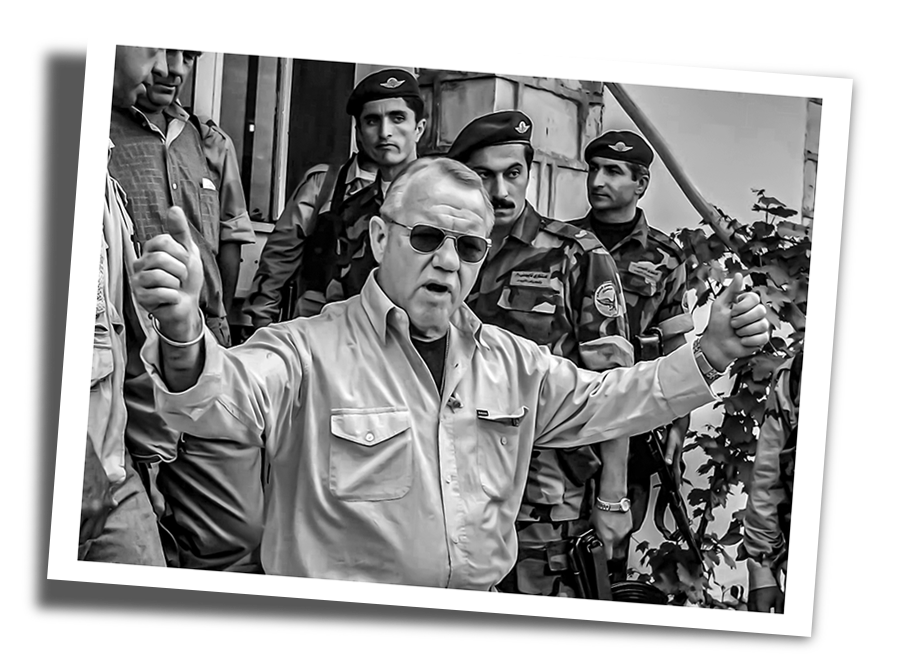

Under-resourced and under-staffed, the ORHA was placed under the command of retired Gen. Jay Garner who, in the words of a 2008 assessment published by the Combat Studies Institute Press, “had 61 days to build an organization, develop interagency plans, coordinate them with CENTCOM, and deploy his team to the theater … an almost impossible set of tasks.”

Impossible – and, ultimately, pointless.

Jay Garner: "I just thought it was necessary to rapidly get the Iraqis in charge of their destiny."

Jay Garner: "I just thought it was necessary to rapidly get the Iraqis in charge of their destiny."

Within three weeks of his arrival in Baghdad on April 11, just two days after the toppling of Saddam’s statue in Fidros Square, Garner was sacked and the ORHA was replaced by the Coalition Provisional Authority.

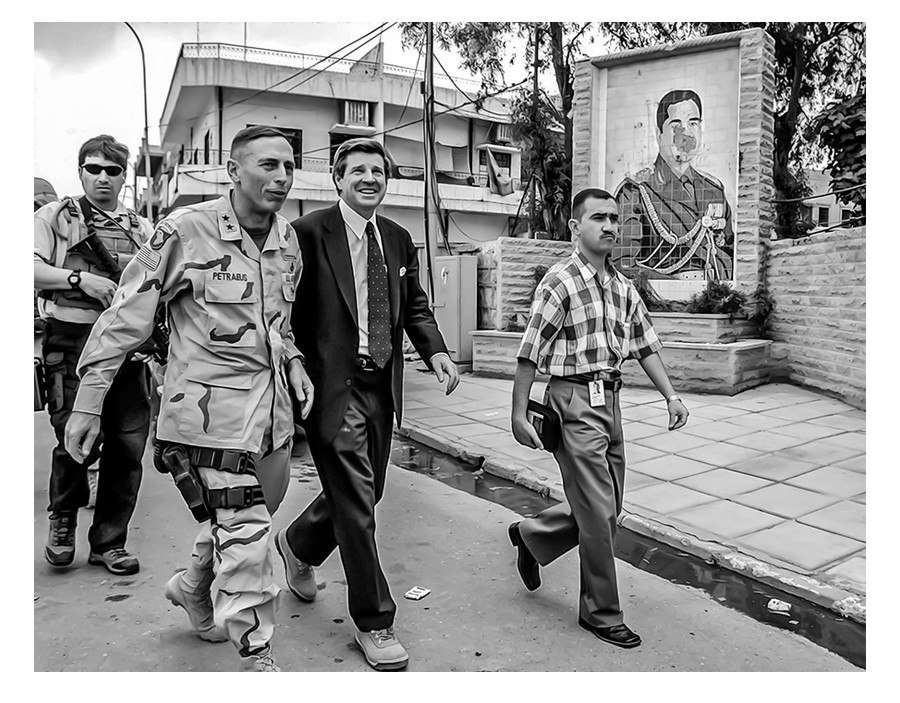

At the helm of the CPA was Paul Bremer, a former career diplomat-turned-businessman who on May 9 was appointed at short notice by Bush as presidential envoy to Iraq. He was subject to the “authority, direction and control” of Rumsfeld, but invested with the power to rule by decree.

Within days he had issued two sweeping decrees that would prove catastrophic.

Garner, his ousted predecessor, had planned to recruit up to 300,000 members of Iraq’s army to help with reconstruction and the restoration of law and order, and also intended to bring back mid-level Baathist managers to keep the wheels of government turning.

He also planned democratic elections to hand control of the country back to Iraqis as soon as possible – a plan that, as he later said, had been approved by everyone from Bush to National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, Rumsfeld, and US Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz.

“My preference was to put the Iraqis in charge as soon as we can, and do it with some form of elections,” Garner told the BBC in March 2004.

“I just thought it was necessary to rapidly get the Iraqis in charge of their destiny, with our firm hand over them, guiding them and helping them.”

But Bremer, who arrived in Baghdad on May 12, had other ideas.

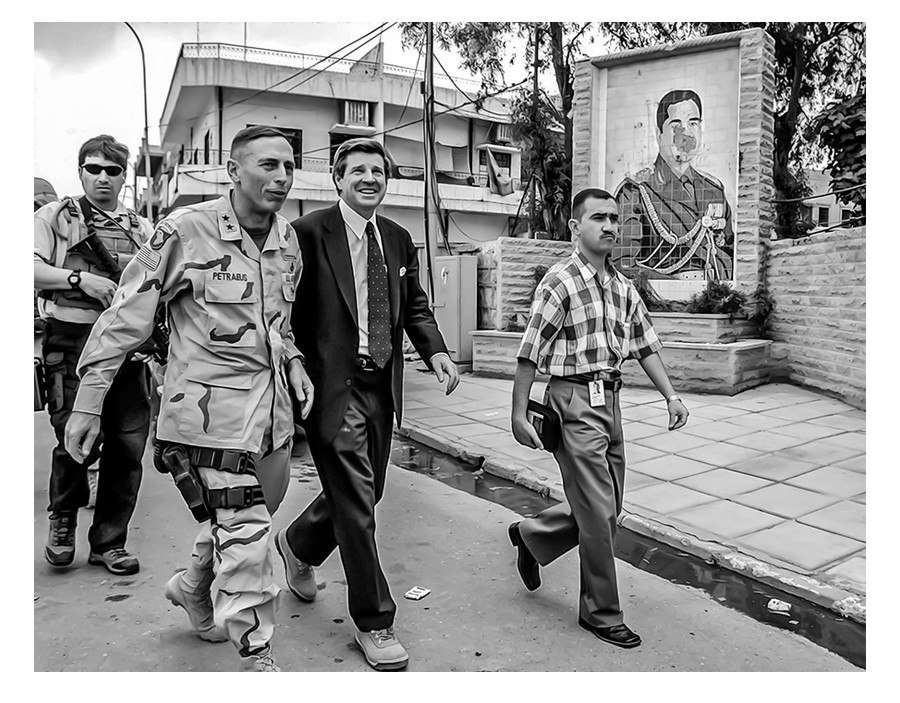

Paul Bremer, accompanied by US commander Maj. Gen. David Petraeus, passes a defaced mural of Saddam Hussein on a visit to Mosul on May 18, 2003. (AFP)

Paul Bremer, accompanied by US commander Maj. Gen. David Petraeus, passes a defaced mural of Saddam Hussein on a visit to Mosul on May 18, 2003. (AFP)

Almost his first act, four days later, was to issue Coalition Provisional Authority Order 1, triggering the “de-Baathification of Iraqi society.”

Everyone in the “top three layers of management” in every national government ministry or institution, including universities and hospitals, was to be screened and, if found to be affiliated with the Baath Party, “removed from their positions and banned from future employment in the public sector.”

This was a broad broom, which took no account of the fact that many people had been members of the party only because their job required them to be. Overnight, the machinery of Iraqi society was deprived of tens of thousands of vital human cogs, from civil servants and bureaucrats to doctors and teachers.

But it was Coalition Provisional Authority Order 2, "Dissolution of Entities," which followed a week later and disbanded Iraq’s army, that really lit the fuse.

Suddenly, instead of being engaged in the rebuilding of their country, as Bremer's predecessor Garner had planned, up to 300,000 trained, armed men were jobless, angry, and on the streets.

Later, when it became apparent that many of the resentful soldiers had joined the insurgency that quickly flared up, ultimately costing the lives of tens of thousands of Iraqis and some 4,000 American soldiers, Bremer claimed he had only been following orders.

In an opinion article for The New York Times in September 2007, he wrote: “It has become conventional wisdom that the decision to disband Saddam Hussein’s army was a mistake, was contrary to American pre-war planning, and was a decision I made on my own.

In fact, he said, “the policy was carefully considered by top civilian and military members of the American government. And it was the right decision.”

But the authors of the US Army’s assessment of the campaign, published in 2019, did not agree.

“Although it was true that many Iraqi Sunnis resented the regime’s removal from power, some Sunnis had hoped the coalition would eventually come to recognize the value of maintaining Sunni prominence in the Iraqi Government,” they wrote.

But Bremer’s first two orders had “obliterated that optimism and turned most Sunnis against the occupation force, lending popular support to the disenfranchised former Iraqi soldiers, Baath Party officials, and Sunni tribes who were eager to expel the coalition presence.”

Worse, the perception grew that Bremer’s CPA was reaching out to Shiite communities and leaders, while failing to work with the Sunni tribes.

In the words of the army’s two-volume debrief, “Sunni leaders viewed themselves as the natural allies of the coalition, as they shared a common enemy – Iran – and in exchange for a (hoped-for) coalition decision to put the Iraqi government in Sunni hands, these tribes intended to keep the Shiite Iranians out of Iraq and split oil revenues with the United States and its coalition partners.”

When Sunni tribal leaders realized that the US intended to allow the Shiites a majority share of the proposed Iraqi Interim Government, “they quickly turned against the coalition, and many began to join forces with other Sunni resistance and terrorist organizations to expel the coalition violently from the Sunni areas of Iraq.”

Over the coming years, Bremer and the CPA would have a lot to answer for.

“Instead of toppling the regime and instituting a transitional government as envisioned in the invasion plans, the US deep de-Baathification policy and decision to dissolve the entire Iraqi security apparatus effectively collapsed the edifice of the Iraqi state, creating a national governance and security vacuum that would take another six to seven years to refill.

“When combined with abortive reconstruction efforts and unmet popular expectations, these factors became major contributors to Iraq’s gradual descent into full insurgency and civil war.”

APRIL 2, 2003:

“Okay, Bubba, we’re here. Now what?”

– Lt. Gen. William Wallace calls Coalition Forces Land Component Command for instructions after the US 3rd Infantry Division seizes downtown Baghdad.

US military planners had estimated it would take between 70 and 120 days to overthrow Saddam Hussein, who had ruled Iraq for the best part of three decades. In fact, his army was routed, and Saddam driven into hiding, in just 21 days.

On April 9, exactly three weeks after the opening shots had been fired in Operation Iraqi Freedom, the dictator made one final public appearance, greeting supporters in front of television cameras in the Baghdad neighborhood of Adhamiya.

That same day, resistance in Baghdad collapsed, the capital fell to the Americans and, here and there, Iraqis began celebrating in the streets.

In one iconic incident on April 9, crowds attacked a 12-meter-tall statue of the deposed dictator in the city’s Firdos Square, which was finally pulled down with the help of a passing unit of US Marines, equipped with an M88 armored recovery vehicle.

Saddam would not be seen again until Dec. 13, when, after seven months on the run, US special forces found him, disheveled, heavily bearded, and confused, hiding in a hole in the ground in a farm compound near his hometown of Tikrit, 150 kilometers northwest of Baghdad.

The Americans had issued a set of 55 playing cards, each bearing the face of a wanted member of the regime and advertising the bounty on offer for turning them in. Saddam, the ace of spades in the pack, was worth $25 million.

But the man who told the Americans where he was hiding, who was Saddam’s bodyguard and a relative, reportedly got nothing, because he revealed his location only after being arrested and interrogated.

The reward offered for Saddam’s sons, Qusay and Uday, the ace of hearts and the ace of clubs in the pack, was $15 million each. They had been killed on July 22 by US soldiers who stormed the house in Mosul in which they were hiding after they refused to surrender. Qusay’s 14-year-old son Mustafa died with them.

The owner of the house, a former regime loyalist who had taken them in, was reported to have been paid in full for betraying them.

On May 1, Bush was back on television once again, broadcasting from the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, which had just returned from the Gulf.

Standing in front of a large banner emblazoned with the stars and stripes and bearing the words “Mission accomplished,” he announced that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended.”

To the whoops and cheers of the crew, he added: “In the battle of Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed.”

It would prove to be a hubristic claim that would come back to haunt the president, and thousands of American and Iraqi families.

The apparent victory had come at a light cost for the coalition. By May 1, just 172 Americans had been killed, along with 33 British troops, and about 24 Kurdish Peshmerga fighters.

Speaking from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, President Bush declares victory in Iraq. (AFP)

Speaking from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, President Bush declares victory in Iraq. (AFP)

It was a different story for the Iraqis, of course, both those in and out of uniform. As many as 45,000 combatants had been killed, along with an estimated 7,200 civilians.

But the war was far from over and, thanks to a tragedy of errors, the body count was set to rise.

It soon became painfully clear to the Americans that overthrowing Saddam had been the easy part.

Few in the region and beyond mourned the passing of the era of Saddam, who had ruled Iraq with a rod of iron and for years had relentlessly persecuted the Kurds in the north of the country.

His invasion of Iran in 1980 had led to a bloody war that had cost the lives of at least half a million Iraqis and as many or more Iranians before it ended in stalemate eight years later, and in 1990 he had brought the entire region to the threshold of catastrophe when he invaded Kuwait in a bid to seize its oil fields.

But in the vacuum left behind in 2003 by the neutering of the ousted dictator’s ruling Baath party, the dismissal of the entire Iraqi army and the lack of serious US planning for a post-war Iraq, the country swiftly descended into years of insurgency, sectarian violence, and civil war, creating the perfect conditions for the emergence of Daesh and the insidious rise of Iranian influence in Iraq’s politics.

It was left to a surprisingly frank two-volume study of the conduct of the war, commissioned by the US Army’s senior leadership in 2013 and finally published in 2018, to admit what the politicians who had started the conflict could never bring themselves to concede.

The human and material cost of the conflict had been “staggering.” But, they added, it was in terms of “geostrategic consequences” that the war had generated its most “profound consequences. With Iraq no longer a threat, Iran’s destabilizing influence has quickly spread.”

In fact, they concluded, “an emboldened and expansionist Iran appears to be the only victor. Iraq, the traditional regional counterbalance for Iran, is at best emasculated, and at worst has key elements of its government acting as proxies for Iranian interests.”

The story of the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq is the story of a catalogue of blunders and missteps by a US administration that assumed Iraqis would welcome democracy with open arms, but reckoned without the agendas of the multiple factions in the country which, freed from the ruthless chains that had bound them together, now sought power and payback for the decades of repression they had endured.

With hindsight, the four-phase plan for the invasion of Iraq that was presented to President Bush and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld by CENTCOM commander Gen. Tommy Franks at Camp David on Dec. 28. 2001 was dangerously naive.

Phases one to three were not the problem: build a coalition of willing partners and supporters, embark on “psychological and military deception operations designed to encourage segments of Iraqi society and its armed forces not to resist”, and, finally, invade Iraq, destroy any forces that had not melted away and “decapitate the Iraqi regime.”

But phase four, so-called post-combat “stability operations,” including the transition of power to a new Iraqi government, was a different matter.

As the clear-eyed US Army analysis of the war noted, too little thought was given to this crucial phase, while such thought that had been given was fatally undermined by a series of flawed assumptions.

Key among these was that “US forces would be welcomed as liberators, and that the Iraqi army would help provide security under a new, more enlightened Iraqi government.”

As a result, the US forces that had focused “on their immediate objectives of destroying the Iraqi military and forcing regime change, were not prepared for the complicated phase four they were about to face.”

Wrong-footed by “overly optimistic strategic assessments that the Iraqi population would welcome the coalition and resume normal activities quickly,” coalition commanders were surprised to find themselves faced with “widespread public disorder and looting,” even as they continued to battle remaining pockets of resistance in Baghdad and Anbar, and much of the north of the country had yet to be secured.

At first, the predictions of a warm welcome appeared valid.

“Once it became clear that Saddam was no longer in power, Iraqi citizens began wild celebrations in the streets of Baghdad and other liberated areas,” read the official US Army analysis of the campaign.

But celebration quickly morphed into something else. Coalition troops “were unprepared for the utter dissolution of public order that followed,” and within days of the collapse of the regime, “Baghdad and other areas of Iraq descended into chaos.”

Baath Party and Iraqi government offices and public facilities, including police stations and hospitals, were attacked, looted and, in some cases, set on fire. Looters descended on the National Museum of Baghdad, and hundreds of priceless artifacts were stolen, many of which would turn up later on international markets.

Here and there, riots began to flare, which in many cases appeared to the military to be orchestrated attempts to provoke a violent response from coalition troops.

Within 10 days of Baghdad’s fall on April 9, religious leaders from various sects had begun jockeying for positions of power in cities throughout the country.

The confusion in post-invasion occupied Iraq was typified by the hurried creation of the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, set up at short notice by the US Department of Defense to support the transition from military to civilian control.

Under-resourced and under-staffed, the ORHA was placed under the command of retired Gen. Jay Garner who, in the words of a 2008 assessment published by the Combat Studies Institute Press, “had 61 days to build an organization, develop interagency plans, coordinate them with CENTCOM, and deploy his team to the theater … an almost impossible set of tasks.”

Impossible – and, ultimately, pointless.

Jay Garner: "I just thought it was necessary to rapidly get the Iraqis in charge of their destiny."

Jay Garner: "I just thought it was necessary to rapidly get the Iraqis in charge of their destiny."

Within three weeks of his arrival in Baghdad on April 11, just two days after the toppling of Saddam’s statue in Fidros Square, Garner was sacked and the ORHA was replaced by the Coalition Provisional Authority.

At the helm of the CPA was Paul Bremer, a former career diplomat-turned-businessman who on May 9 was appointed at short notice by Bush as presidential envoy to Iraq. He was subject to the “authority, direction and control” of Rumsfeld, but invested with the power to rule by decree.

Within days he had issued two sweeping decrees that would prove catastrophic.

Garner, his ousted predecessor, had planned to recruit up to 300,000 members of Iraq’s army to help with reconstruction and the restoration of law and order, and also intended to bring back mid-level Baathist managers to keep the wheels of government turning.

He also planned democratic elections to hand control of the country back to Iraqis as soon as possible – a plan that, as he later said, had been approved by everyone from Bush to National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, Rumsfeld, and US Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz.

“My preference was to put the Iraqis in charge as soon as we can, and do it with some form of elections,” Garner told the BBC in March 2004.

“I just thought it was necessary to rapidly get the Iraqis in charge of their destiny, with our firm hand over them, guiding them and helping them.”

But Bremer, who arrived in Baghdad on May 12, had other ideas.

Paul Bremer, accompanied by US commander Maj. Gen. David Petraeus, passes a defaced mural of Saddam Hussein on a visit to Mosul on May 18, 2003. (AFP)

Paul Bremer, accompanied by US commander Maj. Gen. David Petraeus, passes a defaced mural of Saddam Hussein on a visit to Mosul on May 18, 2003. (AFP)

Almost his first act, four days later, was to issue Coalition Provisional Authority Order 1, triggering the “de-Baathification of Iraqi society.”

Everyone in the “top three layers of management” in every national government ministry or institution, including universities and hospitals, was to be screened and, if found to be affiliated with the Baath Party, “removed from their positions and banned from future employment in the public sector.”

This was a broad broom, which took no account of the fact that many people had been members of the party only because their job required them to be. Overnight, the machinery of Iraqi society was deprived of tens of thousands of vital human cogs, from civil servants and bureaucrats to doctors and teachers.

But it was Coalition Provisional Authority Order 2, "Dissolution of Entities," which followed a week later and disbanded Iraq’s army, that really lit the fuse.

Suddenly, instead of being engaged in the rebuilding of their country, as Bremer's predecessor Garner had planned, up to 300,000 trained, armed men were jobless, angry, and on the streets.

Later, when it became apparent that many of the resentful soldiers had joined the insurgency that quickly flared up, ultimately costing the lives of tens of thousands of Iraqis and some 4,000 American soldiers, Bremer claimed he had only been following orders.

In an opinion article for The New York Times in September 2007, he wrote: “It has become conventional wisdom that the decision to disband Saddam Hussein’s army was a mistake, was contrary to American pre-war planning, and was a decision I made on my own.

In fact, he said, “the policy was carefully considered by top civilian and military members of the American government. And it was the right decision.”

But the authors of the US Army’s assessment of the campaign, published in 2019, did not agree.

“Although it was true that many Iraqi Sunnis resented the regime’s removal from power, some Sunnis had hoped the coalition would eventually come to recognize the value of maintaining Sunni prominence in the Iraqi Government,” they wrote.

But Bremer’s first two orders had “obliterated that optimism and turned most Sunnis against the occupation force, lending popular support to the disenfranchised former Iraqi soldiers, Baath Party officials, and Sunni tribes who were eager to expel the coalition presence.”

Worse, the perception grew that Bremer’s CPA was reaching out to Shiite communities and leaders, while failing to work with the Sunni tribes.

In the words of the army’s two-volume debrief, “Sunni leaders viewed themselves as the natural allies of the coalition, as they shared a common enemy – Iran – and in exchange for a (hoped-for) coalition decision to put the Iraqi government in Sunni hands, these tribes intended to keep the Shiite Iranians out of Iraq and split oil revenues with the United States and its coalition partners.”

When Sunni tribal leaders realized that the US intended to allow the Shiites a majority share of the proposed Iraqi Interim Government, “they quickly turned against the coalition, and many began to join forces with other Sunni resistance and terrorist organizations to expel the coalition violently from the Sunni areas of Iraq.”

Over the coming years, Bremer and the CPA would have a lot to answer for.

“Instead of toppling the regime and instituting a transitional government as envisioned in the invasion plans, the US deep de-Baathification policy and decision to dissolve the entire Iraqi security apparatus effectively collapsed the edifice of the Iraqi state, creating a national governance and security vacuum that would take another six to seven years to refill.

“When combined with abortive reconstruction efforts and unmet popular expectations, these factors became major contributors to Iraq’s gradual descent into full insurgency and civil war.”

A harvest of blood and tears

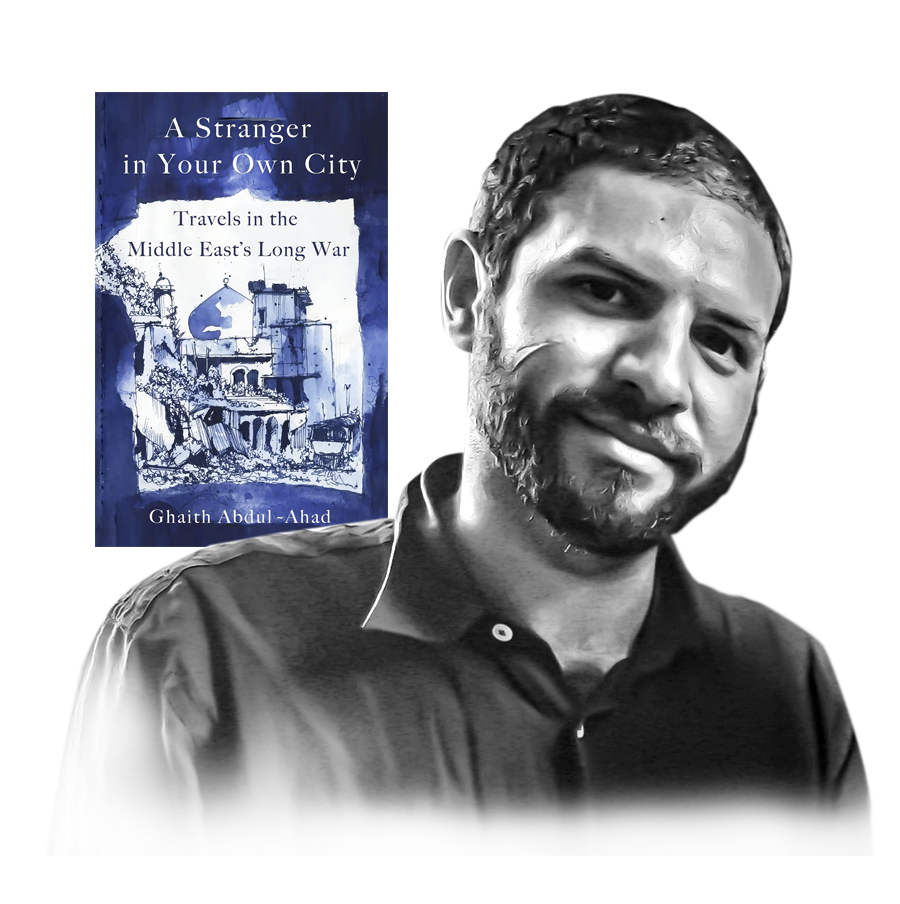

"Iraq, destroyed and occupied, hung between a state and no state. The initial guarded optimism of the Iraqis – who were promised liberation, prosperity, and freedom with the removal of Saddam – shattered with the first car bomb. It became evident that the long-awaited peace was not coming – and that the occupation had unleashed something much worse."

– Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, "A Stranger in Your Own City," Hutchinson Heinemann, March 2023

<<2003-2006–Insurgency and sectarianism

Aug. 7, 2003: A bomb at the Jordanian embassy in Baghdad kills 17. It is the beginning of a series of outrages aimed at coalition or Shiite targets by Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (TJT), or in English, the Group of Monotheism and Jihad, founded by Jordanian-born Salafi jihadist Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi.

Aug. 19, 2003: A truck bomb at the newly opened UN headquarters in Baghdad kills 22, including Sergio Vieira de Mello, UN special representative in Iraq. UN workers withdraw from Iraq.

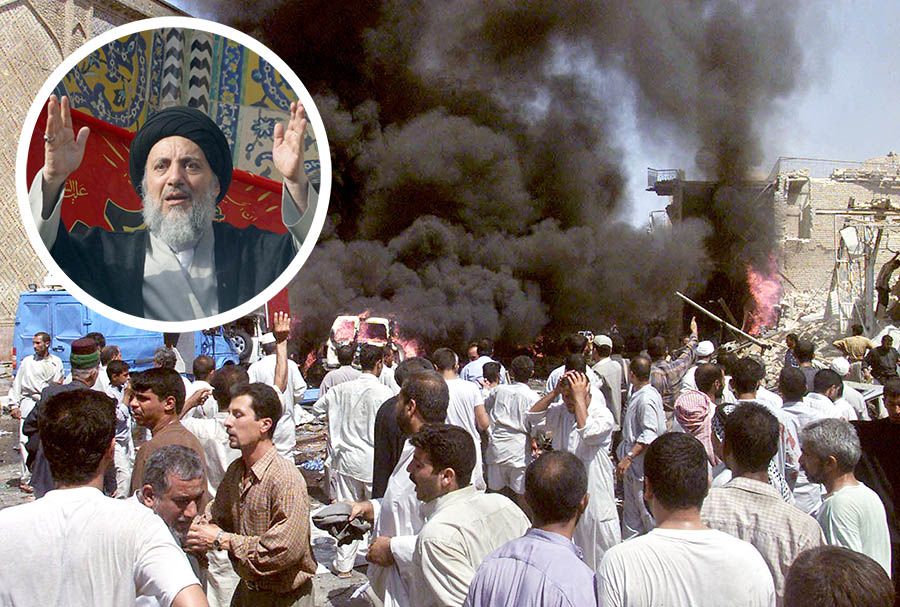

Aug. 28, 2003: A suicide car bomb claims the lives of Mohammed Baqr Al-Hakim, Iraq’s leading Shiite politician, and almost 100 others outside Iraq’s holiest Shiite shrine, the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf.

October-November 2003: Insurgents hit multiple targets in Ramadan offensive, killing 117 American soldiers by the end of October – two more than died in the war Bush had declared over on May 1.

March 2, 2004: Highest single death toll since start of occupation as TJT attacks Shiite worshippers in Baghdad and Karbala, killing 140.

March 31, 2004: Insurgents kill four American private contractors in Fallujah, hanging their burnt and mutilated bodies from a bridge, triggering the first Battle of Fallujah. This costs the lives of 27 Americans and hundreds of Iraqis but fails to dislodge insurgents, and leads to numerous attacks on coalition forces throughout the region.

April 2004: Photographs emerge showing torture and humiliation of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib, a former regime prison being run by the US military 30 kilometers west of Baghdad. The revelations trigger a wave of kidnaps and killings of foreigners by Al-Qaeda in Iraq.

<<2006-2008 – Civil war

Feb. 22, 2006: Bombing of Al-Askari shrine in Samarra by Al-Qaeda in Iraq triggers wave of violence against Sunnis by Shiite militants, leaving hundreds dead, dozens of mosques damaged, and clerics kidnapped and murdered. Sunni militants retaliate, and Iraq is locked in a civil war.

June 7, 2006: Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, founder of TJT, which since 2004 has become Al-Qaeda in Iraq, is killed in targeted US airstrike.

July 9, 2006: Mahdi Army militiamen kill more than 40 Sunni civilians in Baghdad’s Hayy Al-Jihad neighborhood.

Nov. 23, 2006: More than 200 are killed and dozens wounded in car-bomb and mortar attacks on Shiite community in Baghdad’s Sadr City district.

Jan. 10, 2007: Bush announces ‘the surge,’ a deployment of 28,000 extra US troops to Iraq to quell the unrest.

Feb. 3, 2007: More than 130 die in large suicide truck bomb in Baghdad’s open-air Sadriyah market, the deadliest of four attacks in three weeks on Shiite areas.

Jan. 7, 2008: Two suicide bombers kill 14 in Adhamiya, Baghdad, including Riyadh Samarrai, head of one of the US-backed armed Awakening groups fighting Al-Qaeda in Sunni areas.

<<2013-2017 – Battling Daesh

April 8, 2013: Expanding into Syria, jihadist group Islamic State of Iraq changes its name to Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Daesh).

July 21, 2013: Daesh launches Soldier’s Harvest, a 12-month campaign to battle Iraqi security forces and capture territory.

January to August 2014: Daesh captures Fallujah and Mosul, overruns parts of Anbar and Ramadi, captures Sinjar and Zumar, forcing thousands of Yazidis to flee, and seizes border crossings between Syria and Iraq.

August to September 2014: US begins drive against Daesh in Iraq to protect Yazidis and announces formation of broad international coalition to defeat the group.

March to December 2015: Iraq launches major offensive against Daesh, recapturing Tikrit, Ramadi, and country’s largest oil refinery, at Baiji. Kurdish forces take back Sinjar.

June 26, 2016: Iraqi forces, supported by US and coalition airstrikes, recapture Fallujah.

July 3, 2016: A suicide truck bomb, detonated by Daesh at about midnight in Baghdad's Karada district, teeming with people during the last days of Ramadan, kills 250 people.

Oct. 16, 2016, to July 9, 2017: In a lengthy, bloody battle, Iraqi forces finally drive Daesh out of Mosul.

June 21, 2017: Daesh fighters making a last stand at the Grand al-Nuri Mosque in Mosul are defeated by US-backed Iraqi forces. It was here in June 2014 that Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi declared the foundation of the so-called Islamic caliphate.

Dec. 9, 2017: Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi declares victory over Daesh.

2019-2021 – Protests and tensions >>

Hundreds are killed, tens of thousands injured, and thousands more arrested as Iran-backed militias help the government violently to suppress a series of largescale protests against corruption, poor public services, and the sectarian political system imposed by the Americans after 2003.

Dec. 31, 2019: Iran-backed Shiite Kata’ib Hezbollah militia attacks US embassy in Baghdad in response to US airstrikes on the terror group’s bases in Iraq and Syria.

Jan. 3, 2020: Qassem Soleimani, commander of Iran’s special-ops Quds Force, is killed in a US drone strike as his convoy leaves Baghdad airport. Killed with him is Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, a commander of the Popular Mobilization Forces, a collection of armed groups supported by the Iraqi government in the fight against Daesh.

March to September 2020: Terrorist incidents continue throughout Iraq, claiming more than 30 lives. An attack on Camp Taji on March 11 kills two American, and one British, soldiers, provoking US air raids against Kata’ib Hezbollah sites in Karbala, central Iraq. Iraq’s government condemns the US raids.

"Iran the only winner"

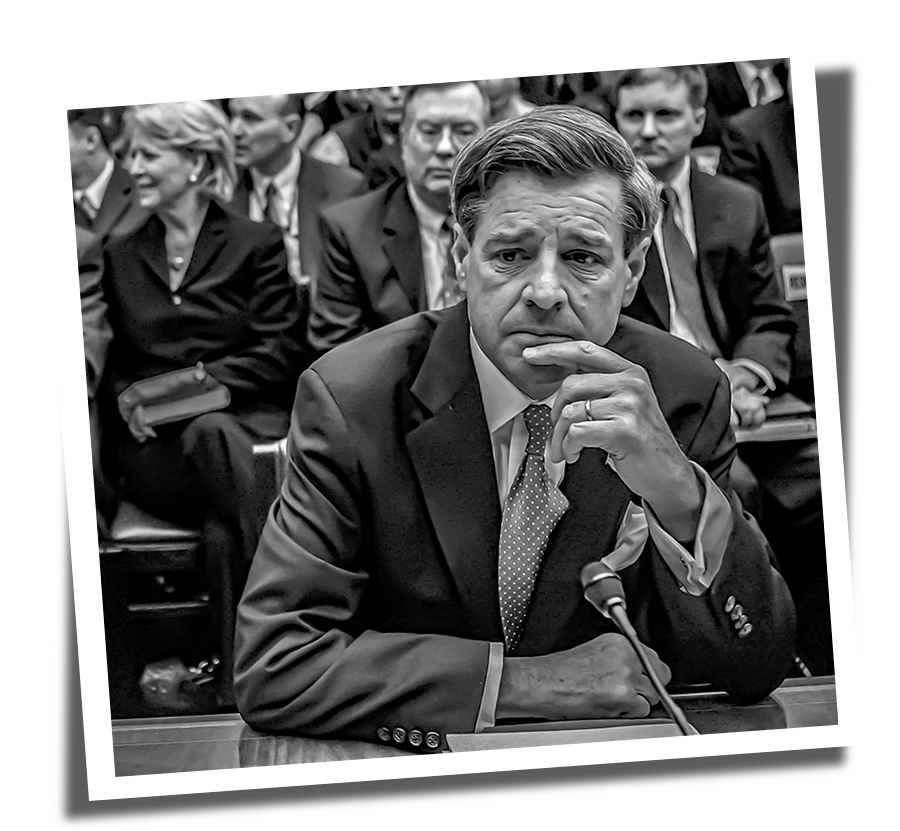

Gen. Raymond Odierno, former commander of US forces in Iraq, ordered a no-holds-barred assessment of the conflict and its aftermath. (AFP)

Gen. Raymond Odierno, former commander of US forces in Iraq, ordered a no-holds-barred assessment of the conflict and its aftermath. (AFP)

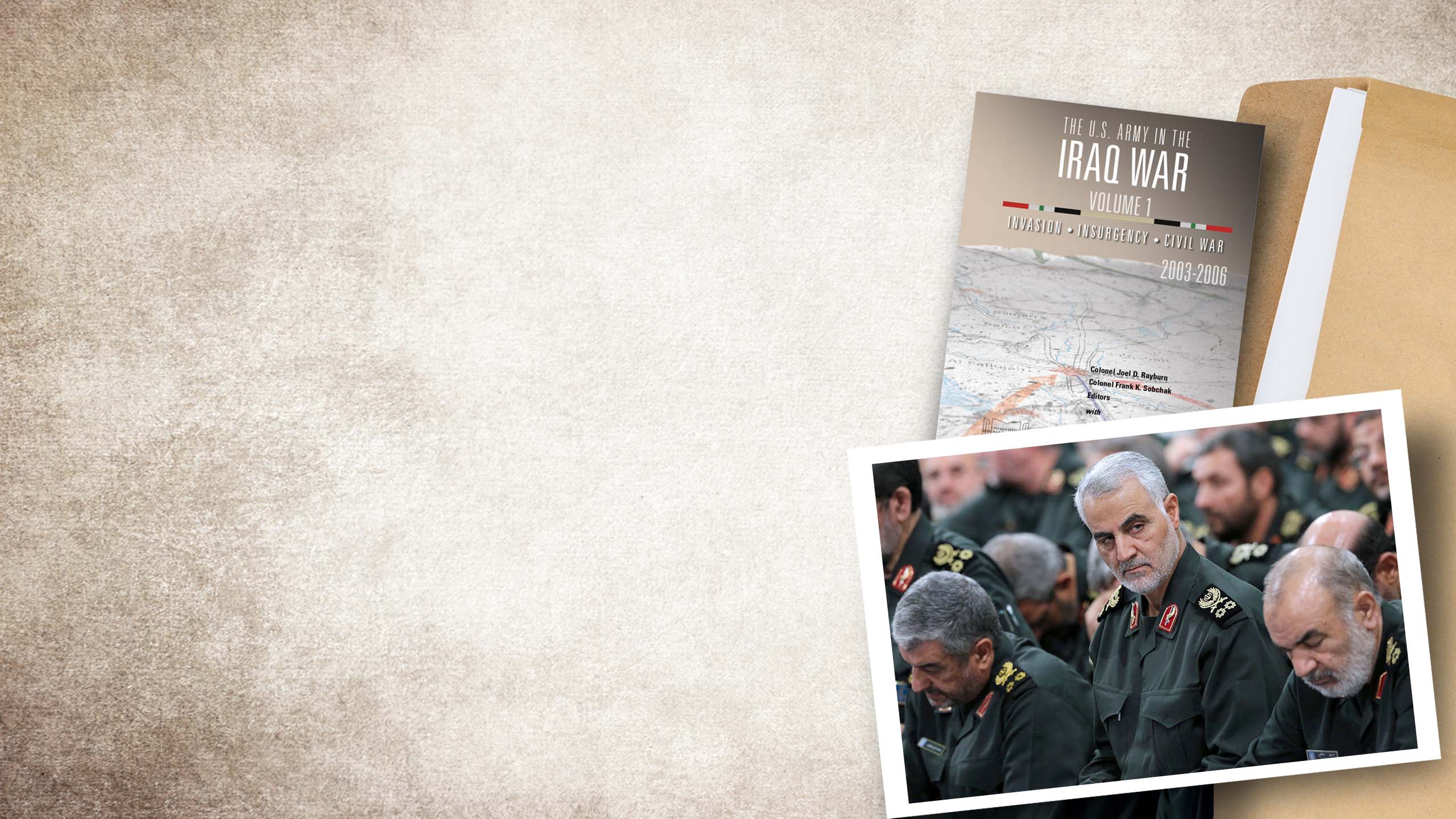

In 2013, Gen. Raymond Odierno, who commanded US forces in Iraq from 2008 to 2010, commissioned an in-depth review of the conduct of the war in Iraq.

Such assessments, designed to identify lessons to be learnt, are common practice in the US military.

But the 1,364-page report, “The US Army in the Iraq War,” delivered a sobering and surprisingly frank assessment, concluding that “an emboldened and expansionist Iran appears to be the only winner” of a rashly conceived and executed misadventure that backfired on the interests of Iraq, the US, and its allies in the region.

The review’s numerous researchers, authors, and editors, drawn mainly from the army’s Strategic Studies Institute and the US Army War College, faced a lengthy, complex task, conducting thousands of hours of interviews and painstakingly analysing tens of thousands of pages of documents, many of which remain classified.

It was 2018 before the Defense Office of Prepublication and Security Review finally cleared the two-volume report for publication, and its findings were controversial.

As the executive summary to volume one noted, Odierno had “challenged the authors to maturely address topics previously considered taboo.”

Accordingly, they had pulled no punches.

Stepping outside the tightly defined parameters of previous studies, which traditionally had restricted their observations to military matters, the authors crossed the line into political territory, resulting in “assessments that at times will strike a critical tone that some readers find unusual for an Army study.”

In short, they concluded, in ridding the region of one perceived threat, the poorly planned and executed US occupation of Iraq after the invasion had merely empowered another.

Iraq, the traditional regional counterbalance for Iran, had been “at best emasculated, and at worst has key elements of its government acting as proxies for Iranian interests.”

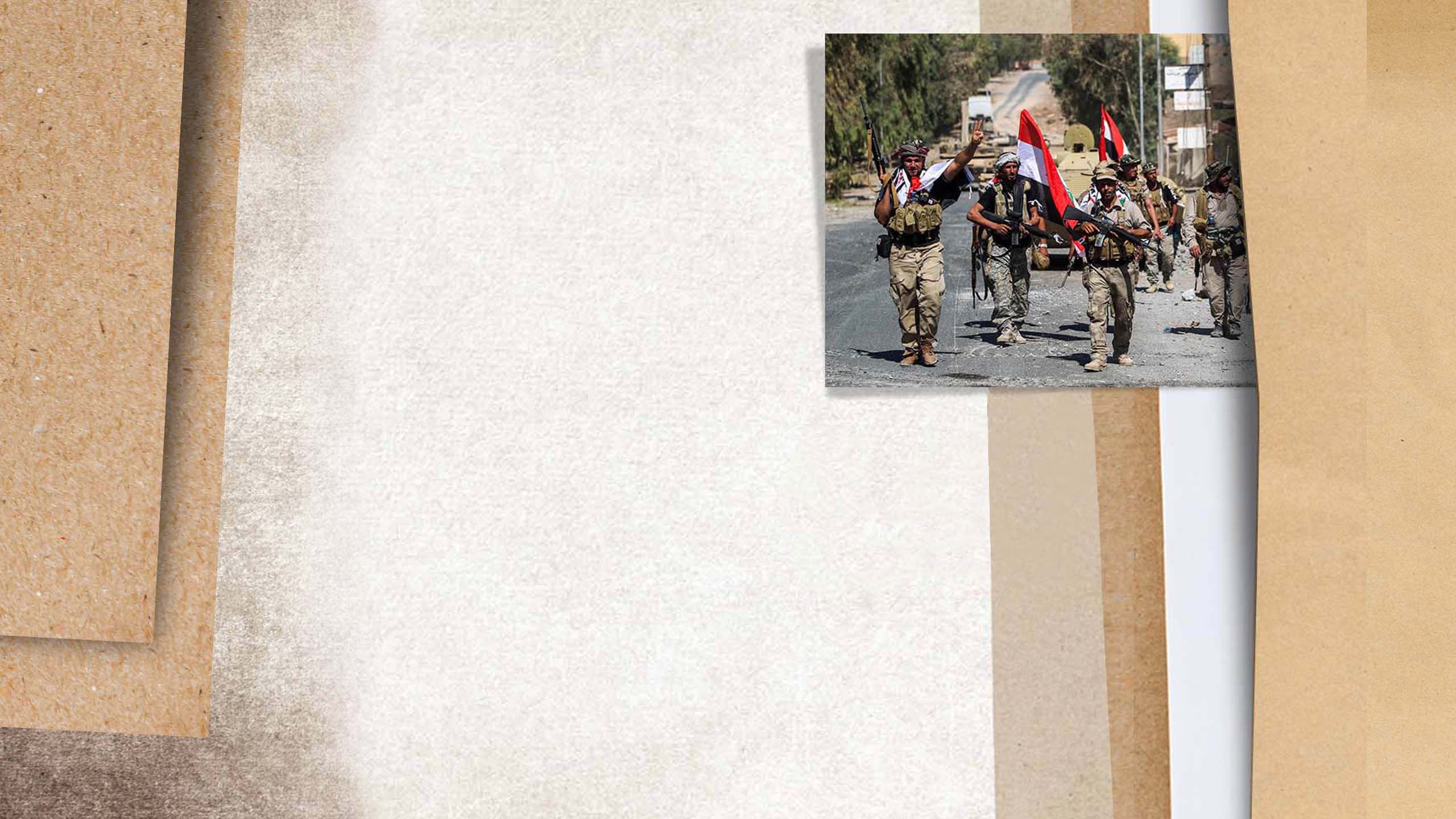

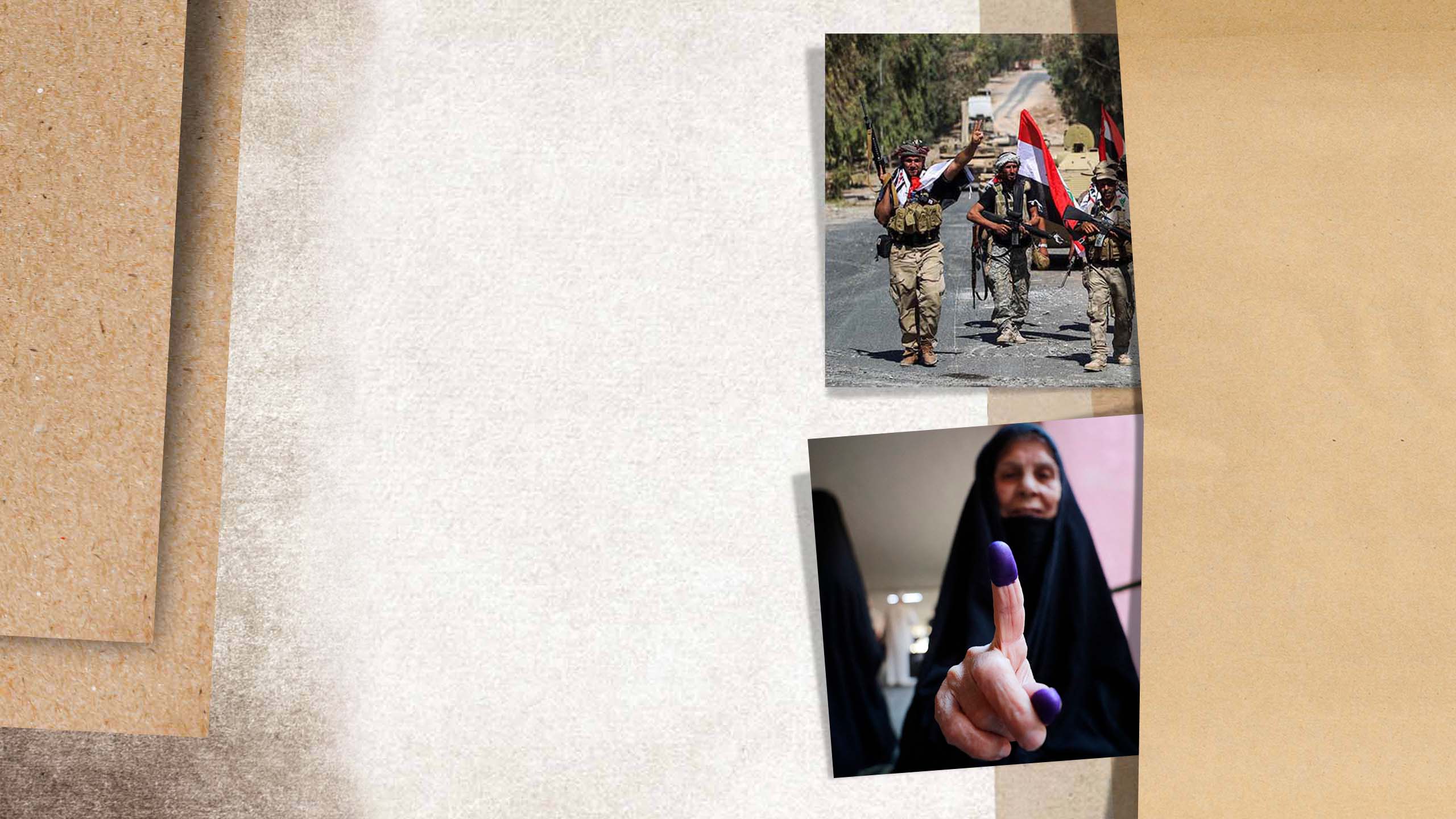

On Jan. 1, 2022, members of Iraq's government-backed Popular Mobilization Forces take to the streets of Baghdad in a tribute to Qasem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, killed in a US drone strike in 2020. (AFP)

On Jan. 1, 2022, members of Iraq's government-backed Popular Mobilization Forces take to the streets of Baghdad in a tribute to Qasem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, killed in a US drone strike in 2020. (AFP)

As a result, “Iran’s destabilizing influence has quickly spread to Yemen ... and Syria, as well as other locations.”

The extent to which Iran had infiltrated Iraqi politics since the 2003 invasion became apparent at around 1 a.m. on Jan. 3, 2020, when a convoy of two vehicles leaving Baghdad International Airport was hit by a salvo of Hellfire missiles from a US drone.

The blazing wreckage of the vehicle in which Qasem Soleimani died in a US drone strike in Baghdad on Jan. 3, 2020.

The blazing wreckage of the vehicle in which Qasem Soleimani died in a US drone strike in Baghdad on Jan. 3, 2020.

Ten men died, but the main target of the attack was Qasem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Force, the special-operations branch of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. He was the man responsible for recruiting, training, and funding the multiple pro-Iranian militias that had sprung up in Iraq after the 2003 invasion, and for directing the policies of the political parties that grew out of them.

Soleimani’s assassination and the events that led up to it highlighted the impunity with which Iranian agents and their proxies had been operating in Iraq in the years since 2003.

The US government had been stung into action by a series of events that began on Dec. 27, 2019, when a US civilian contractor was killed in a rocket attack on an Iraqi military base in Kirkuk by Iranian proxy Kata’ib Hezbollah.

Two days later, in retaliation US aircraft bombed several Kata’ib Hezbollah bases in Iraq and Syria, killing 25 militants. The airstrikes in turn triggered protests in Baghdad, where on New Year’s Eve a large crowd, composed mainly of members of Kata’ib Hezbollah, tried to break into the US embassy.

The aftermath of a US air strike on a Kata’ib Hezbollah base in Iraq's Babylon province in March 2020. (AFP)

The aftermath of a US air strike on a Kata’ib Hezbollah base in Iraq's Babylon province in March 2020. (AFP)

According to US intelligence, Soleimani was behind the events of the previous week, and he was now in Baghdad to orchestrate more mayhem, putting American lives in danger.

Members of Iraq's Popular Mobilization Forces, trained and armed by Iran, attack the US embassy in Baghdad on Dec. 31, 2019, to vent their anger over air strikes that killed pro-Iran fighters. (AFP)

Members of Iraq's Popular Mobilization Forces, trained and armed by Iran, attack the US embassy in Baghdad on Dec. 31, 2019, to vent their anger over air strikes that killed pro-Iran fighters. (AFP)

Soleimani had been in the Americans’ crosshairs before. In January 2007 US special forces tracked a convoy in which he was traveling as it made its way from Iran across the border toward the Kurdish city of Erbil in northern Iraq.

On that occasion, he was spared. But Gen. Stanley McChrystal, who at the time was head of the US military’s Joint Special Operations Command, later wrote that there had been “good reason to eliminate Soleimani” that night in 2007. “At the time, Iranian-made roadside bombs built and deployed at his command were claiming the lives of US troops across Iraq.”

But by 2019, an increasingly emboldened Soleimani had pushed his luck with the Americans too far.

Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, the founder of Kata’ib Hezbollah, was killed alongside Qasem Soleimani on Jan. 3, 2020. (AFP)

Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, the founder of Kata’ib Hezbollah, was killed alongside Qasem Soleimani on Jan. 3, 2020. (AFP)

At the airport, he and his entourage were met by Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, the founder of Kata’ib Hezbollah, and deputy head of Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). Designated a terrorist by the US and other states, Al-Muhandis had been pictured at the scene of the American embassy siege on New Year’s Eve, along with other Iranian-backed militia leaders.

Al-Muhandis too would be killed in the drone attack, and in February 2020 the US also designated his successor, Ahmad Al-Hamidawi, a terrorist.

The PMF had been formed by the Iraqi government in 2014 as an umbrella organization bringing together a diverse collection of dozens of militias with the common aim of battling Daesh. Many, however, including Kata’ib Hezbollah, had been founded and were funded by Iran, and were seen as taking their orders not from the Baghdad government, but from Tehran.

To the Americans, and to Iraqis concerned that their country was becoming an Iranian satellite, the fact that Soleimani was able openly to fly to Baghdad and drive through the streets of the capital – heading to a planned meeting with Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi, a Saddam Hussein-era exile with strong ties to Iran – seemed to underscore the failure of attempts to reinvent Iraq as an independent, democratic country in the wake of the 2003 invasion.

Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi in August 2019. With strong links to Iran, he had been due to meet Qasem Soleimani on the night Iran's Quds Force commander was killed in Baghdad. (AFP)

Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi in August 2019. With strong links to Iran, he had been due to meet Qasem Soleimani on the night Iran's Quds Force commander was killed in Baghdad. (AFP)

As long ago as the 1979 revolution, Iran had begun supporting Iraqi Shiite militias opposed to Saddam. Many of these developed political wings, and, according to an analysis by the Wilson Center in 2020, “by 2017 Iraq had at least 10 parties with ties to Iran.”

Hadi Al-Amiri, leader of the pro-Iranian Badr Organization, during a rally in Basra on April 21, 2018. (AFP)

Hadi Al-Amiri, leader of the pro-Iranian Badr Organization, during a rally in Basra on April 21, 2018. (AFP)

In 2018, ahead of Iraq’s parliamentary elections, eight pro-Iran groups merged to form the Fatah Alliance, led by Hadi Al-Amiri, secretary-general of the Badr Organization, “Iran’s oldest proxy in Iraq, formed by exiles in Iran and initially funded, trained, equipped, and led by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.”

Other Fatah Alliance founder-member groups, all with ties to Iran, included Kata’ib Hezbollah, Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq, and Kata’ib Imam Ali.

In March 2018, two months before elections in Iraq, US Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis said America had “worrisome evidence that Iran is trying to influence — using money — the Iraqi elections.”

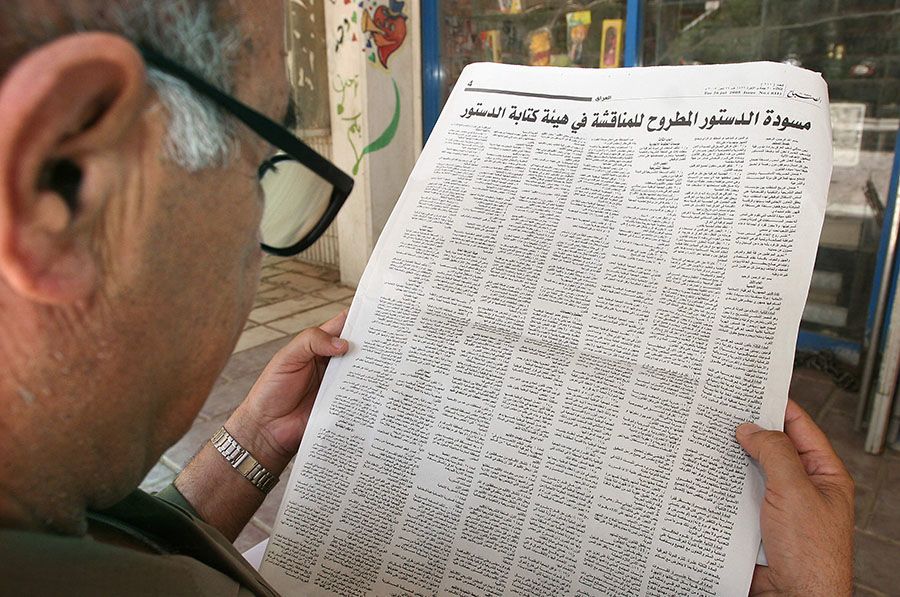

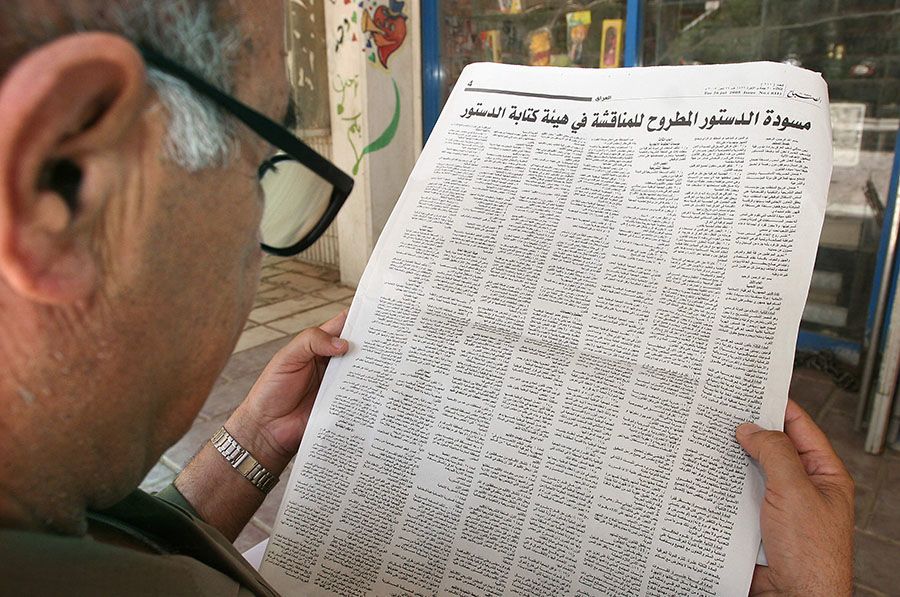

A man in Baghdad reads news of Iraq's new constitution in July 2005. In theory, it prohibits the involvement of foreign organizations in Iraqi politics. (AFP)

A man in Baghdad reads news of Iraq's new constitution in July 2005. In theory, it prohibits the involvement of foreign organizations in Iraqi politics. (AFP)

The involvement in Iraqi politics of Iranian proxy militias and their political wings appears to make nonsense of much of Iraq’s constitution, adopted in 2005. Article 7, for instance, states that “any entity or program that adopts, incites, facilitates, glorifies, promotes, or justifies racism or terrorism ... shall be prohibited” and “may not be part of political pluralism in Iraq.”

Article 9 expressly prohibits “the formation of military militias outside the framework of the armed forces.” Yet not only was Iraq awash with state-sanctioned Iran-backed militias, but it also emerged that they had taken to the streets and joined government forces in suppressing the 2019 protests, killing dozens of protesters in the process.

In an exclusive paper analyzing the role of Iran’s militias in Iraq, published by the Arab News Research and Studies Unit in January, Dr. Azeem Ibrahim, a research professor at the Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, and a director at the Newlines Institute for Strategy and Policy in Washington, D.C., wrote that the international effort to rebuild and reconstitute Iraq had been “fatally undermined by two factors.”

Iraqi militia fighters from Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr's Peace Brigade during fighting with Daesh forces in Salah al-Din province in August 2014. (AFP)

Iraqi militia fighters from Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr's Peace Brigade during fighting with Daesh forces in Salah al-Din province in August 2014. (AFP)

The first was the Sunni terrorist campaign of Al-Qaeda in Iraq, which later became Daesh. The second was “the Shiite terrorism and militia violence largely coordinated and directed by the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.”

Some of the militias “operated with the direct sanction of the-then Iraqi prime minister, Nouri Al-Maliki, under the catch-all title of Special Groups.

“Under the guise of mobilizing the citizenry to defend Iraq, the state allowed the raising of popular militias, many of which were coordinated by pre-existing IRGC front-groups and sectarian militias,” which also fought in Yemen and Syria.

“As the war against Daesh progressed, the influence of the IRGC and the Iranian state over Iraq became more overt and undeniable,” Ibrahim added.

Soleimani “occupied a significant and publicized battlefield role. He had regular meetings not only with Iraqi military figures — many of whom were in IRGC-led militias — but also with the Iraqi president and prime ministers.”

Iraq Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki in December 2009. A former exile in Iran, he returned to Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003. (AFP)

Iraq Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki in December 2009. A former exile in Iran, he returned to Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003. (AFP)

Meanwhile, the Badr Organization, Iran’s oldest proxy in Iraq, “took over the Iraqi interior ministry, and the militias of the PMF entrenched themselves at the heart of the Iraqi government and the economy.”

The Shiite militias, Ibrahim said, “have taken over the Iraqi state and their dominance augers badly for the future of Iraq (and) the people of Iraq, condemned to live in a militia-dominated state ruled by corruption and a conspiracy of silence.”

He added: “Their economy, and their taxes, support the militias. The world is waking up to the terror and crimes of the IRGC and the violent heart of the Islamic Republic. Iraq has suffered for a decade-and-a-half under the same pressures, but its problems remain not only unsolved but, too often, go unnoticed by the wider world.”

Nothing paints the picture of Iranian influence more starkly than the results of Iraq’s parliamentary election in October 2021, the fifth since 2003.

The elections had been brought forward from 2022 in response to the widespread protests that erupted in October 2019, with marches, sit-ins, and demonstrations protesting against everything from sectarianism and Iranian influence in Iraqi politics to unemployment and poor public services.

In the wake of Soleimani’s assassination, banners that had previously proclaimed “Iran out” were replaced by a new slogan, “No to Iran, no to America.”

Jan. 4, 2020: Mourners carry the coffins of slain Iraqi paramilitary chief Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis and Iranian military commander Qasem Soleimani in the Shrine of Imam Hussein in the holy Iraqi city of Karbala. (AFP)

Jan. 4, 2020: Mourners carry the coffins of slain Iraqi paramilitary chief Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis and Iranian military commander Qasem Soleimani in the Shrine of Imam Hussein in the holy Iraqi city of Karbala. (AFP)

Protesters in several towns, including Basra and Nasiriyah, disrupted processions held to mourn the deaths of Soleimani and Al-Muhandis, and in Nasiriyah the local headquarters of the PMF, widely seen as a puppet of Iran, was set on fire.

But Iran’s influence remained undimmed. Of the 329 seats in Iraq's parliament, at least 100 belong to parties that are either affiliated with, or have links to, Tehran. These seats are distributed among three of the largest parliamentary blocs – Fatah Alliance, State of Law Alliance and the Kurdistan Democratic Party.

Following a rift between the Sadrist Movement, which won most seats (73) in 2021, and Iran-aligned parties, the former withdrew from government in June 2022 and the majority of its seats (12) went to Fatah, which represents pro-Iran militia groups.

For award-winning Iraq-born journalist Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, who lived through and reported on the 2003 invasion and its aftermath for The Guardian, and The Washington Post, a straight line can be drawn from the events of 20 years ago to the parlous state of Iraq today.

Iraqi journalist and author Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, right, addressing the UN Security Council in New York on July 17, 2013. (AFP)

Iraqi journalist and author Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, right, addressing the UN Security Council in New York on July 17, 2013. (AFP)

“I think the Americans went to war in Iraq because they could – after 9/11, the Americans were behaving like a wounded bull," he told Arab News.

“Saddam had been getting on the nerves of the Americans for a long time, and Saddam was hated by all his neighbors in the region.

“But they did not calculate the consequences of that war, how the upheavals from that war would affect the region.

“Probably they thought all the Iraqis would welcome an American occupation, that because Saddam was such a brutal dictator, we will all be celebrating.

“But what they didn’t realize was that, yes, people will be happy to get rid of Saddam in the first couple of weeks, but when they see there are no schools, no hospitals, no infrastructure, when the whole ‘Oh, America is coming to change Iraq and turn it into Switzerland,’ doesn’t happen, people will be frustrated, they will be angry, and they will direct this anger toward the Americans.

Ghaith Abdul-Ahad

“So, I wouldn’t say it was a mistake. But it was a kind of criminal negligence for the Americans to just barge into Iraq, topple the regime, and expect democracy to emerge the next day.”

Worse, the new political system that was imposed on Iraq "was built on a system of sectarian and ethnic houses, with the allocation of state institutions based on the sectarian identity of people" and "that created a division in the country – a division that did not exist before."

The result has been "a kleptocratic regime in which politicians, businessmen and militia commanders have total domination of the Iraqi economy. This is why 20 years later, Iraq, with an average of $100 billion of oil money a year, is still on the bottom of every development chart.

"Where is the money going? It is being siphoned off by politicians, businessmen and militia commanders."

There was, he says, a moment of hope in 2019, when "the young generation that grew up after 2003 came of age, and there were demonstrations in the street and the rallying cry was 'We want a homeland'.

"These were pan-sectarian and pan-ethnic demonstrations. They did not achieve a change in the political scene. But it was a spark, showing the people that there is a way forward, that there is another identity for Iraq that is not sectarian, not ethnic, not tribal. And that is the hope for the future of Iraq."

Gen. Raymond Odierno, former commander of US forces in Iraq, ordered a no-holds-barred assessment of the conflict and its aftermath. (AFP)

Gen. Raymond Odierno, former commander of US forces in Iraq, ordered a no-holds-barred assessment of the conflict and its aftermath. (AFP)

In 2013, Gen. Raymond Odierno, who commanded US forces in Iraq from 2008 to 2010, commissioned an in-depth review of the conduct of the war in Iraq.

Such assessments, designed to identify lessons to be learnt, are common practice in the US military.

But the 1,364-page report, “The US Army in the Iraq War,” delivered a sobering and surprisingly frank assessment, concluding that “an emboldened and expansionist Iran appears to be the only winner” of a rashly conceived and executed misadventure that backfired on the interests of Iraq, the US, and its allies in the region.

The review’s numerous researchers, authors, and editors, drawn mainly from the army’s Strategic Studies Institute and the US Army War College, faced a lengthy, complex task, conducting thousands of hours of interviews and painstakingly analysing tens of thousands of pages of documents, many of which remain classified.

It was 2018 before the Defense Office of Prepublication and Security Review finally cleared the two-volume report for publication, and its findings were controversial.

As the executive summary to volume one noted, Odierno had “challenged the authors to maturely address topics previously considered taboo.”

Accordingly, they had pulled no punches.

Stepping outside the tightly defined parameters of previous studies, which traditionally had restricted their observations to military matters, the authors crossed the line into political territory, resulting in “assessments that at times will strike a critical tone that some readers find unusual for an Army study.”

In short, they concluded, in ridding the region of one perceived threat, the poorly planned and executed US occupation of Iraq after the invasion had merely empowered another.

Iraq, the traditional regional counterbalance for Iran, had been “at best emasculated, and at worst has key elements of its government acting as proxies for Iranian interests.”

On Jan. 1, 2022, members of Iraq's government-backed Popular Mobilization Forces take to the streets of Baghdad in a tribute to Qasem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, killed in a US drone strike in 2020. (AFP)

On Jan. 1, 2022, members of Iraq's government-backed Popular Mobilization Forces take to the streets of Baghdad in a tribute to Qasem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, killed in a US drone strike in 2020. (AFP)

As a result, “Iran’s destabilizing influence has quickly spread to Yemen ... and Syria, as well as other locations.”