Battle For The Nile

How will Egypt be impacted by Ethiopia filling its GERD reservoir ?

Ethiopia is not asking too much ... for years the people of Ethiopia have been deprived of their rights to use this resource to extricate themselves from abject poverty.

While we support Ethiopia’s right to development and the need for energy, we request an Ethiopian understanding of the Egyptian water needs that represent the life for our people, without exaggeration.

The dam brings a lot of benefits ... but for these benefits to materialize we have to reach a binding agreement ...Without that we would always be at the mercy of Ethiopia to give it today and close it tomorrow.

This summer, Egypt will lose control of the Nile.

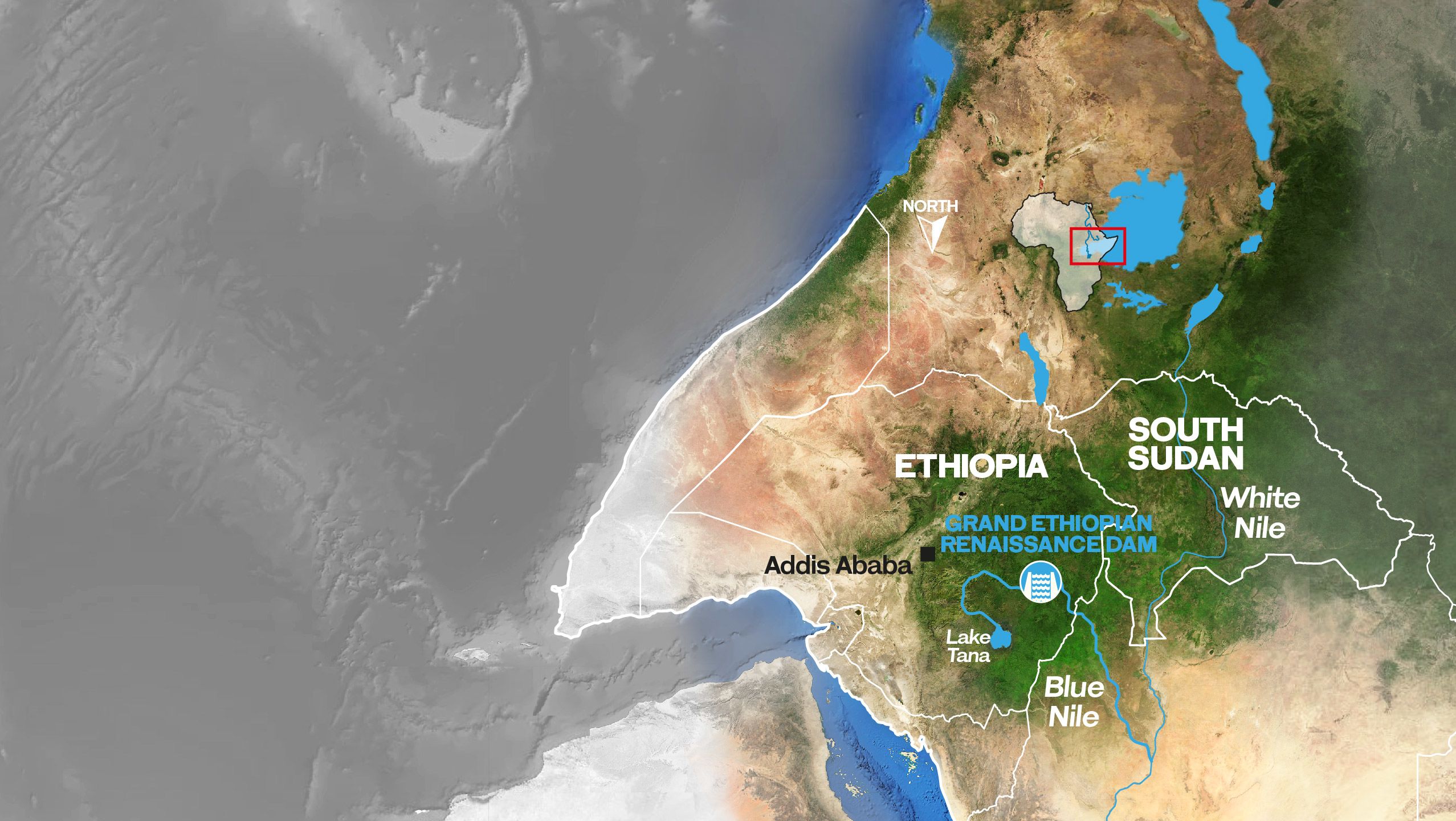

It has been more than 10 years since Ethiopia made the surprise announcement that it planned to build Africa’s largest hydroelectric dam on the Blue Nile, the source of most of Egypt’s fresh water.

At the time, a distracted Egypt was convulsed by social and political upheaval, and Ethiopia started work on the dam almost immediately.

Since then, the prospect has loomed as an existential threat over Egypt, a nation created by and utterly dependent upon the life-giving waters that have flowed down from the Ethiopian Highlands since time immemorial.

“Egypt is suffering no matter what”

Lake Nasser, one of the largest manmade bodies of water in the world, was created when Egypt built the Aswan High Dam between 1960 and 1970. (Getty Images)

Lake Nasser, one of the largest manmade bodies of water in the world, was created when Egypt built the Aswan High Dam between 1960 and 1970. (Shutterstock)

Now that prospect is poised to become a reality. After years of delays, construction of the controversial Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is all but complete and, with the summer rains expected to fall on the Ethiopian Highlands at any moment, the filling of the reservoir it has created is about to begin in earnest.

Nothing is more important to Egypt than the Nile, which runs through the nation’s history, economy and psyche. The country is, as the fifth-century Greek historian Herodotus observed, “the gift of the Nile.” It was the river’s bounty that allowed Egyptian civilization to take root along its banks and flourish in the fertile soils of the Nile Delta, rejuvenated annually by the rich silt deposited by the seasonal flooding of the mighty waterway.

“Without the River Nile, there is no country”

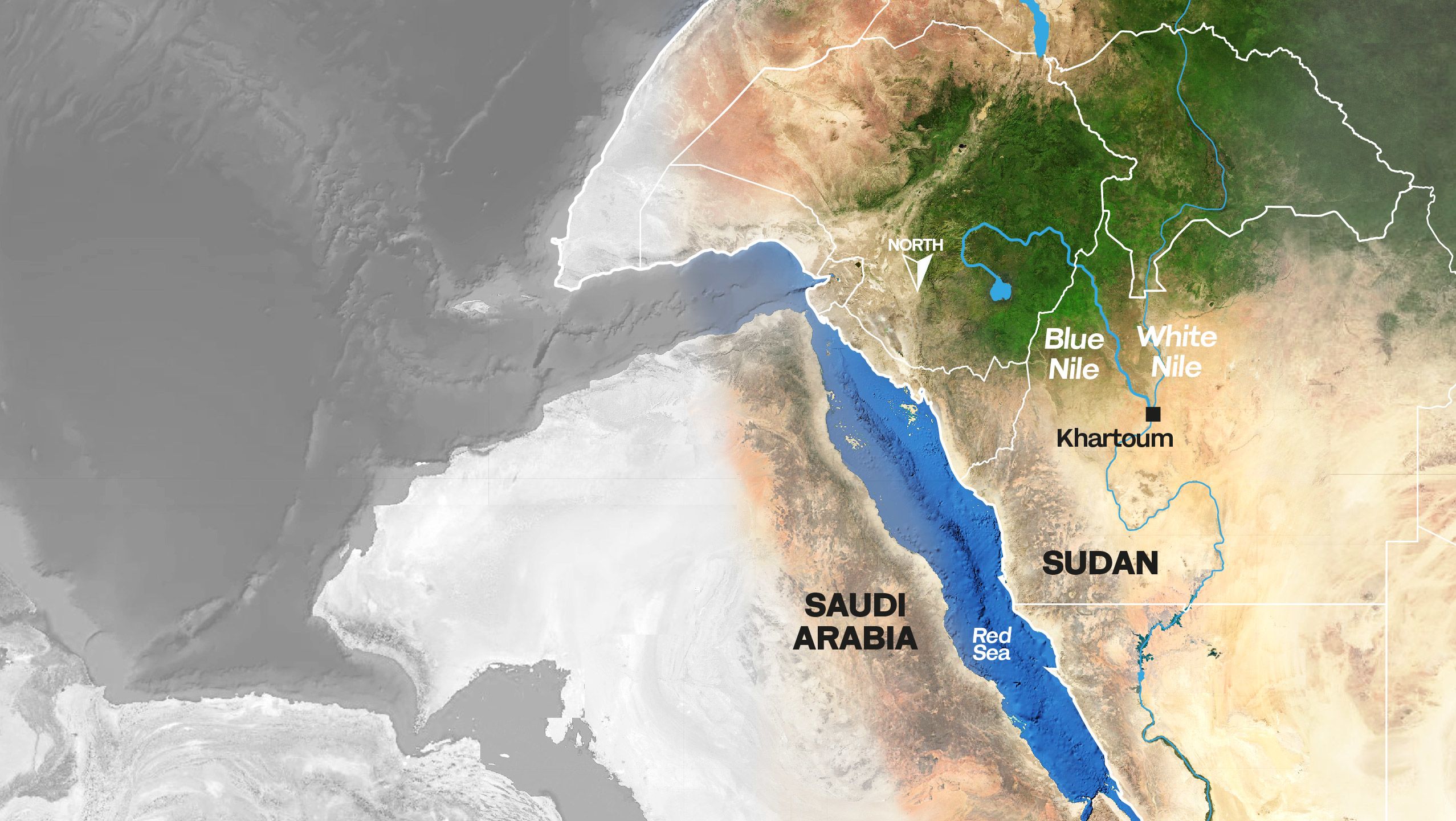

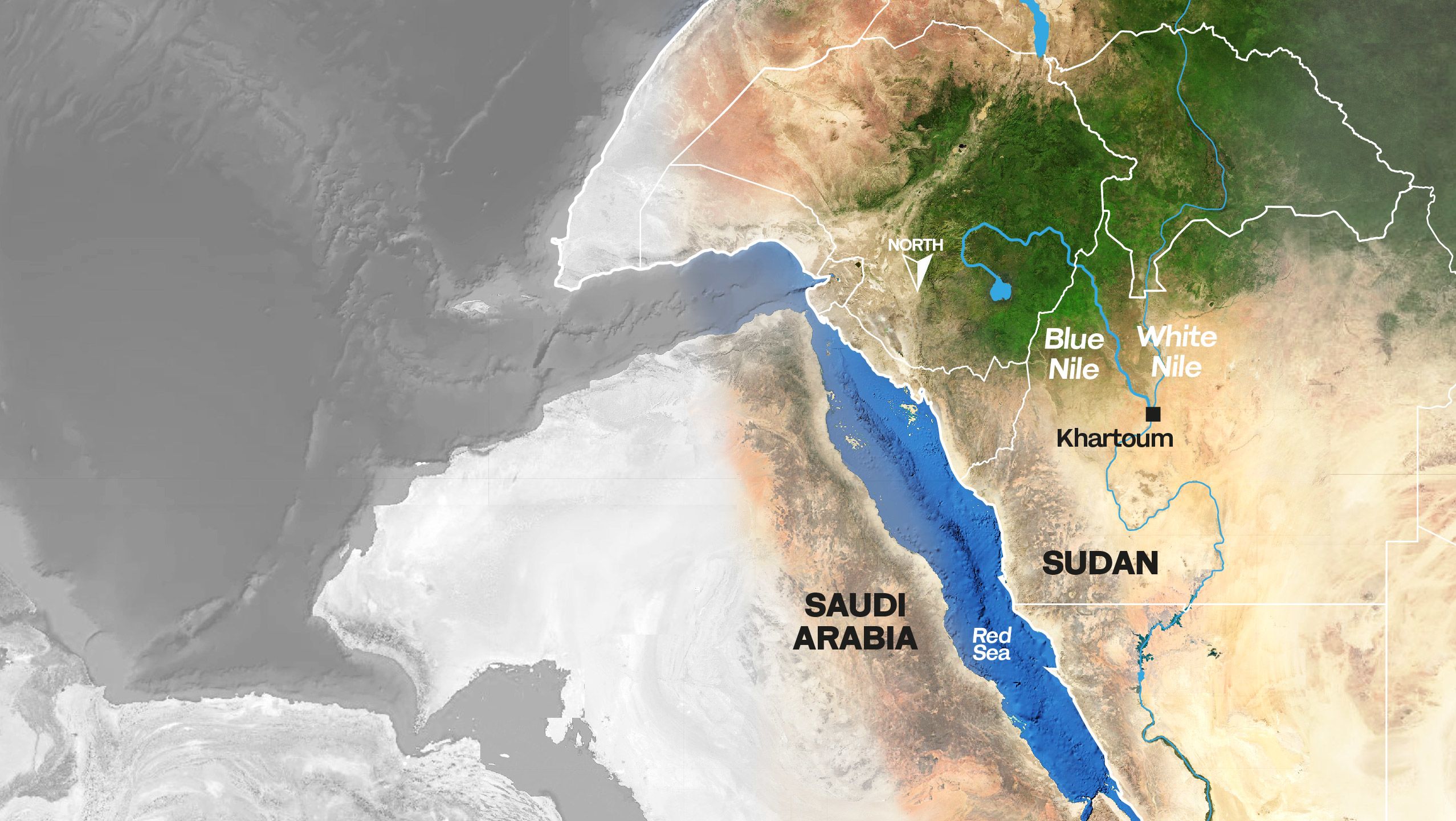

The Nile is fed by two main tributaries, the White Nile and the Blue Nile, which meet at Khartoum in Sudan, Egypt’s immediate southern neighbor. Of the two, the Blue Nile, originating in Lake Tana in Ethiopia, is the source of most of the water that flows through Sudan and into Egypt.

Farmers at work in Sohag, "the Bride of the Nile." Egyptian agriculture is utterly dependent upon water from the river. (Shutterstock)

Farmers at work in Sohag, "the Bride of the Nile." Egyptian agriculture is utterly dependent upon water from the river. (Shutterstock)

The arguments that have raged over the past decade, and the failure of Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan to reach an agreement over how the vast hydroelectric dam should be filled and operated, are now history. The immediate and crucial question right now is – how quickly will Ethiopia fill the GERD reservoir?

“The High Aswan Dam will be like a sick person”

When full, the reservoir will hold 74 billion cubic meters (BCM) of water — almost half as much as the 55 BCM Egypt currently gets from the Nile each year. Fill it too quickly, says Cairo, and Egypt will be deprived of water, devastating its all-important agricultural sector and disrupting its economy, leaving its people short of food and throwing millions out of work. It also fears that, if the level of water in Lake Nasser drops significantly, the amount of electricity generated by the hydroelectric turbines in the Aswan High Dam will be dramatically reduced.

Egypt has demanded that, in order to reduce the impact on itself and Sudan, Ethiopia should take at least 12 years to fill the reservoir and, depending on the amount of annual rainfall, as many as 20 years.

Ethiopia, on the other hand, is desperate to see the GERD reservoir filled, and a return on its $4 billion investment, as soon as possible — within five or seven years, it says, depending on the volume of the seasonal rains.

“There needs to be some minimum flow guaranteed for Egypt”

This summer, Egypt will lose control of the Nile.

It has been more than 10 years since Ethiopia made the surprise announcement that it planned to build Africa’s largest hydroelectric dam on the Blue Nile, the source of most of Egypt’s fresh water.

At the time, a distracted Egypt was convulsed by social and political upheaval, and Ethiopia started work on the dam almost immediately.

Since then, the prospect has loomed as an existential threat over Egypt, a nation created by and utterly dependent upon the life-giving waters that have flowed down from the Ethiopian Highlands since time immemorial.

“Egypt is suffering no matter what”

Lake Nasser, one of the largest manmade bodies of water in the world, was created when Egypt built the Aswan High Dam between 1960 and 1970. (Getty Images)

Lake Nasser, one of the largest manmade bodies of water in the world, was created when Egypt built the Aswan High Dam between 1960 and 1970. (Shutterstock)

Now that prospect is poised to become a reality. After years of delays, construction of the controversial Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is all but complete and, with the summer rains expected to fall on the Ethiopian Highlands at any moment, the filling of the reservoir it has created is about to begin in earnest.

Nothing is more important to Egypt than the Nile, which runs through the nation’s history, economy and psyche. The country is, as the fifth-century Greek historian Herodotus observed, “the gift of the Nile.” It was the river’s bounty that allowed Egyptian civilization to take root along its banks and flourish in the fertile soils of the Nile Delta, rejuvenated annually by the rich silt deposited by the seasonal flooding of the mighty waterway.

“Without the River Nile, there is no country”

The Nile is fed by two main tributaries, the White Nile and the Blue Nile, which meet at Khartoum in Sudan, Egypt’s immediate southern neighbor. Of the two, the Blue Nile, originating in Lake Tana in Ethiopia, is the source of most of the water that flows through Sudan and into Egypt.

Farmers at work in Sohag, "the Bride of the Nile." Egyptian agriculture is utterly dependent upon water from the river. (Shutterstock)

Farmers at work in Sohag, "the Bride of the Nile." Egyptian agriculture is utterly dependent upon water from the river. (Shutterstock)

The arguments that have raged over the past decade, and the failure of Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan to reach an agreement over how the vast hydroelectric dam should be filled and operated, are now history. The immediate and crucial question right now is – how quickly will Ethiopia fill the GERD reservoir?

“The High Aswan Dam will be like a sick person”

When full, the reservoir will hold 74 billion cubic meters (BCM) of water — almost half as much as the 55 BCM Egypt currently gets from the Nile each year. Fill it too quickly, says Cairo, and Egypt will be deprived of water, devastating its all-important agricultural sector and disrupting its economy, leaving its people short of food and throwing millions out of work. It also fears that, if the level of water in Lake Nasser drops significantly, the amount of electricity generated by the hydroelectric turbines in the Aswan High Dam will be dramatically reduced.

Egypt has demanded that, in order to reduce the impact on itself and Sudan, Ethiopia should take at least 12 years to fill the reservoir and, depending on the amount of annual rainfall, as many as 20 years.

Ethiopia, on the other hand, is desperate to see the GERD reservoir filled, and a return on its $4 billion investment, as soon as possible — within five or seven years, it says, depending on the volume of the seasonal rains.

“There needs to be some minimum flow guaranteed for Egypt”

Despite Egypt's fears, Ethiopia seems to be on track to fill the reservoir sooner rather than later. In the summer of 2020, it held back 4.9 billion cubic meters of the annual flow of the Blue Nile — just 6.6 percent of the reservoir’s total capacity — in order to test two of the dam’s 16 electricity-generating turbines. This year, however, as the filling of the reservoir begins in earnest, Ethiopia says it plans to capture a further 13.5 BCM, bringing the volume held in the reservoir to as much as 25 percent of its total capacity. If filling continues at the same annual rate, the reservoir could be completely full in just four more years — by the end of the rainy season in 2025.

“Water for Ethiopia is like oil for the Middle East”

For Ethiopians, the dam is a symbol of hope, pride and a brighter future. Half of Ethiopia’s population of 112 million has no access to electricity and still relies on burning wood for heat, cooking and light. At full capacity, the hydroelectric dam will not only boost national industrialization and revolutionize the living standards of millions of its citizens but will also earn the country badly needed income as an exporter of power to the region.

Just how important the project is to Ethiopians became clear when the country struggled to find international backers for the wildly ambitious project. Undeterred, in one of the most remarkable crowd-funding exercises ever seen, over the past decade millions of Ethiopians, many with little or no money to spare but all dreaming of a brighter future, invested what they could in government-issued bonds to fund the dam’s construction.

“The people believe this dam will transform their lives”

The dam will transform the lives of millions in Ethiopia who, like this woman in Lalibela, lack electricity and rely on firewood. (Getty Images)

The dam will transform the lives of millions in Ethiopia who, like this woman in Lalibela, lack electricity and rely on firewood. (Getty Images)

This is truly a people’s dam, as Ethiopia’s social-media users affirm as they count down excitedly to this summer’s historic filling of the dam — on Twitter, hashtags including “ItsMyDam,” “FillTheDam” and “EthiopiaNileRights” abound.

Sudan, Ethiopia’s immediate downstream neighbor, is less apprehensive about the dam than Egypt. It stands to benefit from the cheap electricity that will be generated and also recognizes that the dam has the potential to end the annual cycle of devastating floods that plagues the country, destroying lives and limiting Sudan's agricultural potential. With the flow of water regulated, Sudan’s farmers should be able to cultivate the rich lands flanking the Blue Nile throughout the year.

The storage upstream of vast amounts of water could also help to alleviate the suffering of dry years: Ethiopia was hit by devastating droughts, blamed on changing global weather patterns, in 2008, 2011 and, most recently, in 2015.

Nevertheless, lacking agreement with Ethiopia over the operation of the GERD, Sudan can take nothing for granted. It is particularly concerned about the possible impact on its own hydroelectric Roseires Dam, just 115 kilometers downstream and as dependent as Egypt’s Aswan High Dam on the flow of the Blue Nile for the generation of electricity.

Floods in Sudan in September 2020 destroyed 100,000 homes and left 100 people dead. By regulating the flow of the Blue Nile, Ethiopia's dam could end such devastation. (Getty Images)

Floods in Sudan in September 2020 destroyed 100,000 homes and left 100 people dead. By regulating the flow of the Blue Nile, Ethiopia's dam could end such devastation. (Getty Images)

Sudan would also pay a high price were the dam to suffer a catastrophic failure — a possibility that has been raised in several academic papers. One recent study by Egyptian civil and water engineers highlighted “the high risk of soil instability” in the area of the GERD site, which is “located on one of the major tectonic plates and faults in the world.” Around that fault, about 16 earthquakes with a magnitude of 6.5 or higher occurred in Ethiopia during the 20th century.

Another 250 kilometers downstream from the Roseires Dam is Sudan’s Sennar Dam, built for irrigation purposes in the 1920s. The Egyptian study predicts that, in the event of a breach of the GERD, the resulting flood would swamp the Sennar Dam and inundate land for hundreds of kilometers, as far north as Khartoum City.

Egypt fears that the faster the dam is filled, the more it will suffer. So how quickly should Ethiopia fill the dam?

Egypt fears that the faster the dam is filled, the more it will suffer. So how quickly should Ethiopia fill the dam?

Despite Egypt's fears, Ethiopia seems to be on track to fill the reservoir sooner rather than later. In the summer of 2020, it held back 4.9 billion cubic meters of the annual flow of the Blue Nile — just 6.6 percent of the reservoir’s total capacity — in order to test two of the dam’s 16 electricity-generating turbines. This year, however, as the filling of the reservoir begins in earnest, Ethiopia says it plans to capture a further 13.5 BCM, bringing the volume held in the reservoir to as much as 25 percent of its total capacity. If filling continues at the same annual rate, the reservoir could be completely full in just four more years — by the end of the rainy season in 2025.

“Water for Ethiopia is like oil for the Middle East”

For Ethiopians, the dam is a symbol of hope, pride and a brighter future. Half of Ethiopia’s population of 112 million has no access to electricity and still relies on burning wood for heat, cooking and light. At full capacity, the hydroelectric dam will not only boost national industrialization and revolutionize the living standards of millions of its citizens but will also earn the country badly needed income as an exporter of power to the region.

Just how important the project is to Ethiopians became clear when the country struggled to find international backers for the wildly ambitious project. Undeterred, in one of the most remarkable crowd-funding exercises ever seen, over the past decade millions of Ethiopians, many with little or no money to spare but all dreaming of a brighter future, invested what they could in government-issued bonds to fund the dam’s construction.

“The people believe this dam will transform their lives”

The dam will transform the lives of millions in Ethiopia who, like this woman in Lalibela, lack electricity and rely on firewood. (Getty Images)

The dam will transform the lives of millions in Ethiopia who, like this woman in Lalibela, lack electricity and rely on firewood. (Getty Images)

This is truly a people’s dam, as Ethiopia’s social-media users affirm as they count down excitedly to this summer’s historic filling of the dam — on Twitter, hashtags including “ItsMyDam,” “FillTheDam” and “EthiopiaNileRights” abound.

Sudan, Ethiopia’s immediate downstream neighbor, is less apprehensive about the dam than Egypt. It stands to benefit from the cheap electricity that will be generated and also recognizes that the dam has the potential to end the annual cycle of devastating floods that plagues the country, destroying lives and limiting Sudan's agricultural potential. With the flow of water regulated, Sudan’s farmers should be able to cultivate the rich lands flanking the Blue Nile throughout the year.

The storage upstream of vast amounts of water could also help to alleviate the suffering of dry years: Ethiopia was hit by devastating droughts, blamed on changing global weather patterns, in 2008, 2011 and, most recently, in 2015.

Nevertheless, lacking agreement with Ethiopia over the operation of the GERD, Sudan can take nothing for granted. It is particularly concerned about the possible impact on its own hydroelectric Roseires Dam, just 115 kilometers downstream and as dependent as Egypt’s Aswan High Dam on the flow of the Blue Nile for the generation of electricity.

Floods in Sudan in September 2020 destroyed 100,000 homes and left 100 people dead. By regulating the flow of the Blue Nile, Ethiopia's dam could end such devastation. (Getty Images)

Floods in Sudan in September 2020 destroyed 100,000 homes and left 100 people dead. By regulating the flow of the Blue Nile, Ethiopia's dam could end such devastation. (Getty Images)

Sudan would also pay a high price were the dam to suffer a catastrophic failure — a possibility that has been raised in several academic papers. One recent study by Egyptian civil and water engineers highlighted “the high risk of soil instability” in the area of the GERD site, which is “located on one of the major tectonic plates and faults in the world.” Around that fault, about 16 earthquakes with a magnitude of 6.5 or higher occurred in Ethiopia during the 20th century.

Another 250 kilometers downstream from the Roseires Dam is Sudan’s Sennar Dam, built for irrigation purposes in the 1920s. The Egyptian study predicts that, in the event of a breach of the GERD, the resulting flood would swamp the Sennar Dam and inundate land for hundreds of kilometers, as far north as Khartoum City.

Egypt fears that the faster the dam is filled, the more it will suffer. So how quickly should Ethiopia fill the dam?

Egypt fears that the faster the dam is filled, the more it will suffer. So how quickly should Ethiopia fill the dam?

Some threats posed by the GERD are less obvious but no less potentially devastating. Egypt’s Nile Delta, on average only one meter above sea level at the Mediterranean coast, is already slowly sinking, thanks in part to the relentless grinding of tectonic plates but also to a reduction in the amount of sediment being deposited in the delta every year. Scientists blame this loss of sediment on the creation of Egypt’s Aswan High Dam between 1960 and 1970, as a price paid for the generation of electricity and stabilization of water supplies. But recent studies predict this problem will be “seriously exacerbated” by the operation of the GERD.

Over the past decade, despite numerous attempts at negotiation and mediation, all efforts to reach an agreement between the three countries on the crucial issues of how the dam should be filled and operated, especially during periods of drought, have failed.

"The crux of the matter is that the downstream countries want to retain the current status quo"

Cairo continues to insist that Ethiopia’s decision to, in effect, seize control of the river flies in the face of exclusive rights Egypt was granted to the waters of the Nile under treaties struck with Great Britain in 1929 and between itself and Sudan in 1959. Ethiopia, determined to accelerate its development and become a significant regional player, says such colonial-era agreements, which excluded all the other nine countries that today share the Nile basin, have no currency in the modern age.

In the absence of agreement, the specter of conflict has loomed over the on-off negotiations, and the region remains in the grip of a dangerous stalemate. In June 2013, several Egyptian politicians were accidentally broadcast live on television while discussing military options to halt the dam during a meeting with then-President Mohammed Morsi. Proposals discussed ranged from backing Ethiopian rebels to sending in special forces to destroy the dam.

More recently, on March 2, in what some commentators have interpreted as an ominous development, Egypt and Sudan signed a military cooperation agreement. Four days later, in a speech during a visit to Khartoum, Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi said: “We reject the policy of imposing a fait accompli and extending control over the Blue Nile through unilateral measures without taking the interests of Sudan and Egypt into account.”

At the end of March, the Egyptian president appeared to up the stakes even further. “Egypt’s water is a red line,” he said. “No one can take a single drop of water from Egypt.”

“The impact will be even more during the dry years, which needs cooperation between the countries”

Yet the dam is now a reality, and Ethiopia has pledged to press ahead with filling the reservoir during the upcoming rainy season, with or without the agreement of Egypt or Sudan. And, unless the three countries can come quickly to an agreement, Egypt and Sudan can now do little other than wait and see if their worst fears are to be realized.

Ethiopians express their support for "their" dam during prayers in Addis Ababa at the end of Ramadan in May. (AFP)

Ethiopians express their support for "their" dam during prayers in Addis Ababa at the end of Ramadan in May. (AFP)

For the tens of millions of Ethiopians eagerly awaiting the filling of the dam, harnessing the power of the Blue Nile may prove to be no less transformational than the discovery of "black gold" was for the lives of the Arabs of the oil-rich Gulf states.

For the tens of millions of Egyptians and Sudanese downstream who rely on the Nile for their lives and livelihoods, the coming months and years will be a time of anxiety. They can only wait to see how quickly the GERD reservoir will be filled and how the operation of the dam will impact on water flow over the coming decades, especially during inevitable periods of drought.

“This is going to be a historic moment for humanity in general ... if this gets out of control"

Some threats posed by the GERD are less obvious but no less potentially devastating. Egypt’s Nile Delta, on average only one meter above sea level at the Mediterranean coast, is already slowly sinking, thanks in part to the relentless grinding of tectonic plates but also to a reduction in the amount of sediment being deposited in the delta every year. Scientists blame this loss of sediment on the creation of Egypt’s Aswan High Dam between 1960 and 1970, as a price paid for the generation of electricity and stabilization of water supplies. But recent studies predict this problem will be “seriously exacerbated” by the operation of the GERD.

Over the past decade, despite numerous attempts at negotiation and mediation, all efforts to reach an agreement between the three countries on the crucial issues of how the dam should be filled and operated, especially during periods of drought, have failed.

"The crux of the matter is that the downstream countries want to retain the current status quo"

Cairo continues to insist that Ethiopia’s decision to, in effect, seize control of the river flies in the face of exclusive rights Egypt was granted to the waters of the Nile under treaties struck with Great Britain in 1929 and between itself and Sudan in 1959. Ethiopia, determined to accelerate its development and become a significant regional player, says such colonial-era agreements, which excluded all the other nine countries that today share the Nile basin, have no currency in the modern age.

In the absence of agreement, the specter of conflict has loomed over the on-off negotiations, and the region remains in the grip of a dangerous stalemate. In June 2013, several Egyptian politicians were accidentally broadcast live on television while discussing military options to halt the dam during a meeting with then-President Mohammed Morsi. Proposals discussed ranged from backing Ethiopian rebels to sending in special forces to destroy the dam.

More recently, on March 2, in what some commentators have interpreted as an ominous development, Egypt and Sudan signed a military cooperation agreement. Four days later, in a speech during a visit to Khartoum, Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi said: “We reject the policy of imposing a fait accompli and extending control over the Blue Nile through unilateral measures without taking the interests of Sudan and Egypt into account.”

At the end of March, the Egyptian president appeared to up the stakes even further. “Egypt’s water is a red line,” he said. “No one can take a single drop of water from Egypt.”

“The impact will be even more during the dry years, which needs cooperation between the countries”

Yet the dam is now a reality, and Ethiopia has pledged to press ahead with filling the reservoir during the upcoming rainy season, with or without the agreement of Egypt or Sudan. And, unless the three countries can come quickly to an agreement, Egypt and Sudan can now do little other than wait and see if their worst fears are to be realized.

Ethiopians express their support for "their" dam during prayers in Addis Ababa at the end of Ramadan in May. (AFP)

Ethiopians express their support for "their" dam during prayers in Addis Ababa at the end of Ramadan in May. (AFP)

For the tens of millions of Ethiopians eagerly awaiting the filling of the dam, harnessing the power of the Blue Nile may prove to be no less transformational than the discovery of "black gold" was for the lives of the Arabs of the oil-rich Gulf states.

For the tens of millions of Egyptians and Sudanese downstream who rely on the Nile for their lives and livelihoods, the coming months and years will be a time of anxiety. They can only wait to see how quickly the GERD reservoir will be filled and how the operation of the dam will impact on water flow over the coming decades, especially during inevitable periods of drought.

“This is going to be a historic moment for humanity in general ... if this gets out of control"

Reduction in the water share of Egypt will result in abandoning huge areas of agricultural lands and scattering millions of families.

Any threat to the flow of the Nile is a direct threat to Egypt’s national survival ... The expected effects of GERD on Egypt’s water security are high and may be disastrous, especially during the filling ... If the filling is synchronized with a flood period below the average, the effects will be catastrophic.

Egypt is already facing severe water shortages ... Despite Ethiopia’s claims that hydropower projects will cause no harm, the unilateral filling and operation of Ethiopia’s dam would quickly make matters far worse for both Egypt and Sudan, causing serious environmental and socioeconomic damage.

Nobody will be permitted to take a single drop of Egypt's water, otherwise the region will fall into unimaginable instability ... any act of hostility is detestable ... but our reaction in the event that we are affected will affect the stability of the entire region.

Monitor the water levels

in Ethiopia and Egypt

Click on the links below to see the daily change in water flow and storage at the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, and the impact this is having on Egypt’s Aswan High Dam.

The satellite-based Nile Basin Reservoir Advisory System (NiBRAS) has been developed by Hisham Eldardiry, an Egyptian civil and environmental engineer with the Sustainability Research Group at the University of Washington, Seattle. It has been developed to support the transparent monitoring of reservoir operations in the Nile basin.

The satellite-based Nile Basin Reservoir Advisory System (NiBRAS) has been developed by Hisham Eldardiry, an Egyptian civil and environmental engineer with the Sustainability Research Group at the University of Washington, Seattle. It has been developed to support the transparent monitoring of reservoir operations in the Nile basin.

Credits

Writer: Jonathan Gornall

Research: Jonathan Gornall, Leen Fouad

Editor: Tarek Ali Ahmad

Creative director: Simon Khalil

Designers: Omar Nashashibi, Steve Willard

Graphics: Douglas Okasaki

Video producer: Mohammed Qenan

Video editor: Hasenin Fadhel

Opening animation: Google Earth

Picture researcher: Sheila Mayo

Simulation development: Harold Jacinto

Copy editor: Sarah Mills

Social media: Jad Bitar, Kateryna Kadabashy

Producer: Arkan Aladnani

Editor-in-Chief: Faisal J. Abbas